Ouadi el-Jarf

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.5601-195f |

IdRef IdRef | 197285570 |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 2011 |

Fouille du site portuaire du Ouadi el-JarfOpération de terrain 17132

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Association mer Rouge-Sinaï (AMeRS)

🔗 Antiquities Endowment Fund (ARCE) (AEF (ARCE))

🔗 Honor Frost Foundation

Cofinancements

🔗 Association mer Rouge-Sinaï (AMeRS)

🔗 Antiquities Endowment Fund (ARCE) (AEF (ARCE))

🔗 Honor Frost Foundation

Dates des travaux

mars - juin

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2022 : 10.4000/baefe.8001

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.5504

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.2674

2020 : 10.4000/baefe.117

➣ Site(s) de la mission

http://www.orient-mediterranee.com/spip.php?article911

Participants en 2024

Restauration des papyrus du ouadi el-JarfAction spécifique 20452

Le site du Ouadi el-Jarf se trouve sur la côte du golfe de Suez, un peu au sud du débouché du grand corridor du Ouadi Araba, qui connecte la vallée du Nil à la mer Rouge à la latitude du Fayoum. Il s’agit, avec Ayn Soukhna et Mersa Gaouasis, de l’un des trois ports intermittents de l’époque pharaonique qui ont été récemment identifiés sur ce rivage. Ces installations avaient toutes été aménagées pour pouvoir gagner par voie maritime soit le sud de la péninsule du Sinaï (où les Égyptiens exploitaient les mines de cuivre et de turquoise) soit le plus lointain Pays de Pount, dans la région du Bab el-Mandab. Elles n’étaient occupées que ponctuellement, lorsque l’État égyptien souhaitait organiser des expéditions navales, qui n’avaient sans doute lieu qu’à un rythme quinquennal, ou décennal. Ces opérations étaient particulièrement difficiles à organiser : pour pouvoir embarquer sur la côte, il fallait préalablement traverser le désert oriental en transportant en pièces détachées les embarcations en bois de conifère que l’on souhaitait y utiliser, qu’il était ensuite nécessaire de réassembler sur le rivage. Pour s’épargner autant que possible cette opération pénible et délicate, ces éléments de bateaux n’étaient pas rapportés dans la vallée du Nil une fois l’expédition terminée. Ils étaient laissés sur place, avec le reste du matériel nécessaire à ces expéditions, parfois pendant plusieurs années, en attente de leur réutilisation. C’est pour cette raison que l’élément le plus caractéristique de ces ports intermittents est la présence, à faible distance de la côte, d’un système de galeries-magasins où l’on pouvait entreposer ces embarcations après les avoir à nouveau démontées.

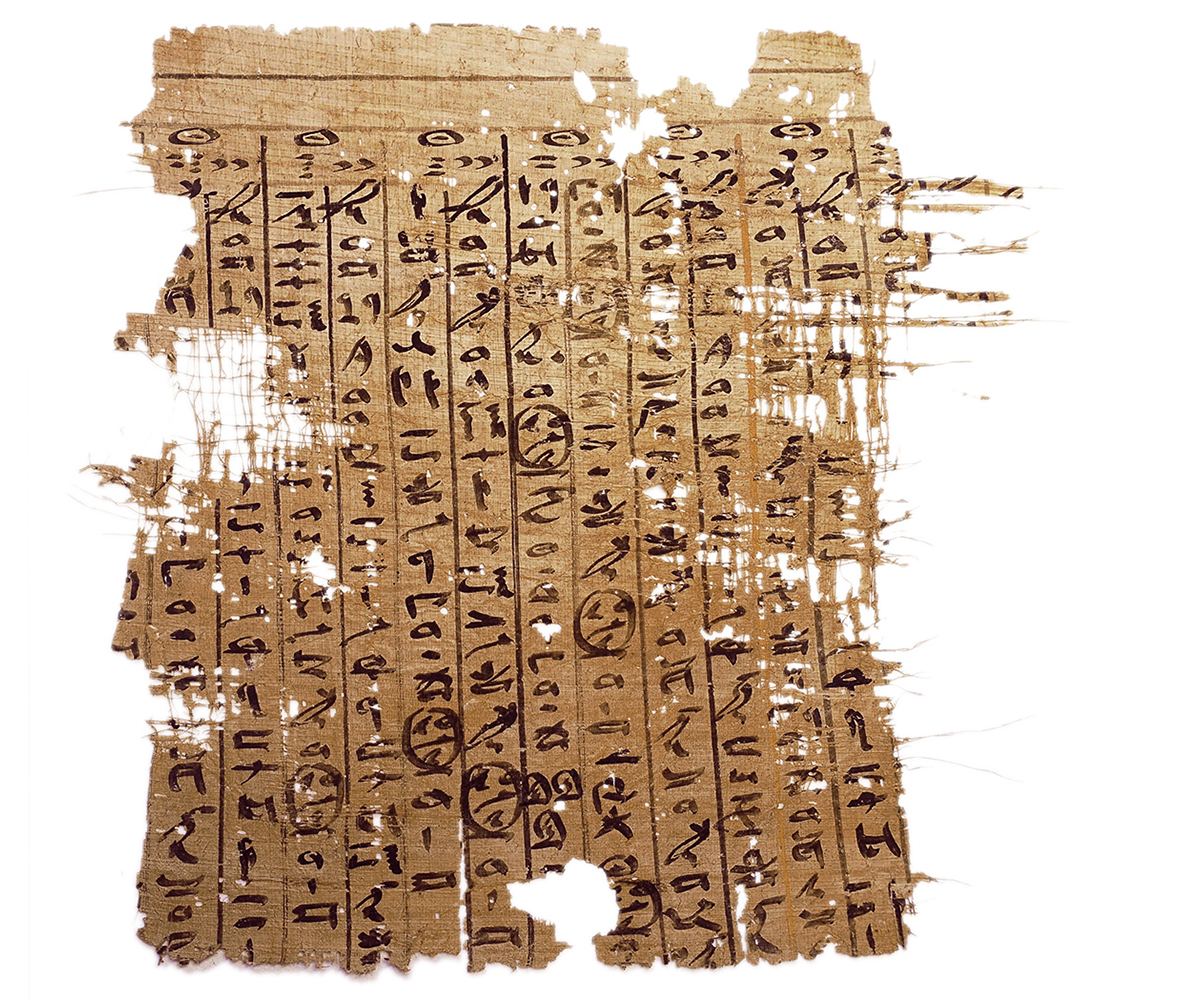

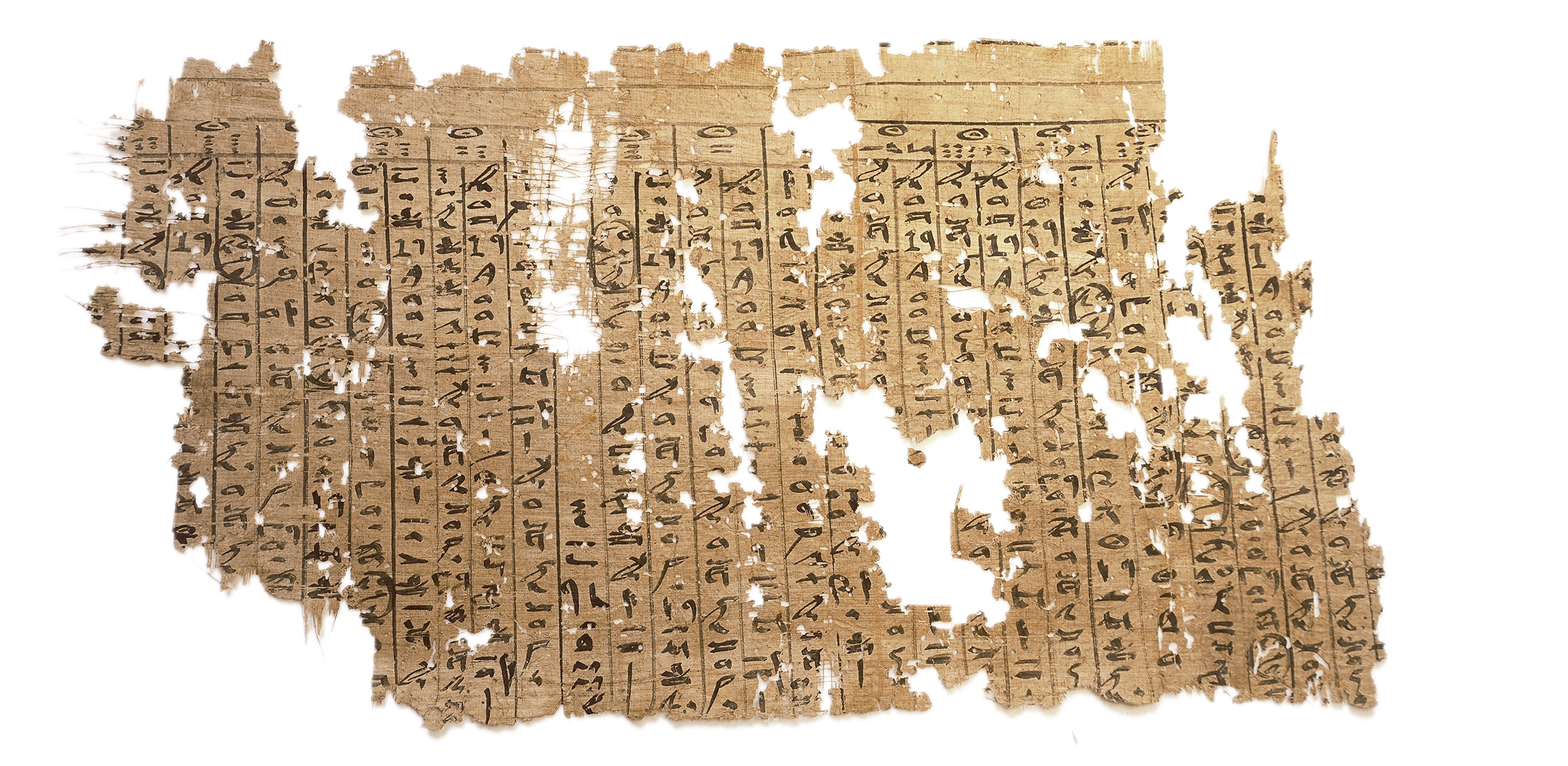

Le site du Ouadi el-Jarf est très certainement la première expérimentation de ce type d’aménagement portuaire. L’ensemble du matériel qui a été découvert sur le site au terme de neuf campagnes de fouilles (2011-2019), et notamment un très abondant ensemble d’inscriptions et de textes, démontre en effet qu’il n’a sans doute été occupé que de façon très brève, pendant le règne des deux premiers rois de la IVe dynastie – Snéfrou et Chéops (env. 2600-2500 av. J.-C.). Le choix de cette implantation a été motivé par plusieurs facteurs favorables, dont l’un des plus importants est la présence d’une source abondante, aujourd’hui incluse dans le monastère de Saint-Paul, à une dizaine de kilomètres des installations antiques, qui permettait d’approvisionner en eau les troupes relativement nombreuses que l’on y envoyait en mission. Sur la côte, les installations portuaires elles-mêmes ont été aménagées à l’aplomb d’une brèche dans le récif corallien qui longe le littoral, ce qui permettait d’accéder sans danger au rivage. À cet endroit fut également construite une jetée massive en forme de L, orientée au nord, qui mesure 200 m d’est en ouest, et 200 m du nord au sud. Elle était destinée à fournir un abri contre le vent et les courants aux embarcations, et il s’agit très certainement à l’heure actuelle des vestiges les plus anciens d’un port artificiel aménagé en milieu maritime. À proximité du port, plusieurs bâtiments à cellules avaient également été construits afin de loger temporairement les équipes qui étaient envoyées en mission. Un ensemble de plus de 100 ancres de bateaux, qui y avaient été soigneusement entreposées en attente de réutilisation, y a été mis au jour. Enfin, un système impressionnant de galeries-magasins, comprenant plus d’une trentaine de ces cavités (dont l’extension varie entre 15 m et plus d’une trentaine de mètres) avaient été creusées dans un calcaire de bonne qualité, dans les derniers contreforts du massif du Gebel Galala, à quelque 5 km de la côte. C’est de la fouille de cet ensemble de galeries, qui sont toutes dotées d’un système impressionnant de fermeture constitué de gros blocs de calcaire, qu’un matériel très abondant datant du début de la IVe dynastie (céramiques, outils, scellés, fragments d’embarcation) a été régulièrement recueilli. Mais la découverte la plus remarquable fut celle, lors de la campagne de fouilles de 2013, d’un très important ensemble de papyrus qui avaient été laissés dans l’entrée de l’une de ces galeries. Il s’agit de documents variés, comprenant à la fois des comptabilités et des journaux de bord, qui appartenaient à l’une des équipes qui avait fréquenté le site à la fin du règne de Chéops, et qui y furent abandonnés au moment du départ de cette troupe, probablement lors de la dernière occupation significative du port. Des centaines de fragments, ayant sans doute appartenu originellement à une trentaine de rouleaux distincts, furent ainsi mis au jour : il s’agit, à l’heure actuelle, des plus anciens papyrus inscrits connus. La surprise fut aussi de constater qu’une partie importante de cette documentation concernait en fait le chantier de construction de la pyramide de Chéops à Giza, pour lequel l’équipe propriétaire de cette documentation avait travaillé quelques mois avant d’être envoyée sur la côte de la mer Rouge. Le « journal de Merer », rapport quotidien d’un petit fonctionnaire qui est indiscutablement un témoin oculaire de l’édification de ce prestigieux monument, apporte ainsi de précieuses informations sur le transport des matériaux de construction qui étaient destinés à la Grande Pyramide. La seule présence de ce lot d’archives sur le site du Ouadi el-Jarf confirme en outre le lien étroit qui existait entre cet aménagement portuaire et le chantier de Chéops à Giza, le port ayant sans doute permis de se procurer, au terme de la traversée du golfe de Suez à cette latitude, le cuivre nécessaire à l’outillage des bâtisseurs du monument.

Pierre Tallet (Sorbonne Université, UMR 8167)

The site of Wadi el-Jarf is located on the Gulf of Suez coast, a little to the south of where the great dry valley of Wadi Araba, which connects the Nile Valley with the Red Sea at the latitude of the Fayoum, opens out. Like Ayn Soukhna and Mersa Gawasis, it is one of the three intermittently-used harbours of the Pharaonic era which have recently been identified on this coast. All these locations were maintained so as to be able to reach either the southern end of the Sinai Peninsula by sea (where Egyptians exploited copper and turquoise mines) or the further-away Land of Punt, in the region of Bab el-Mandab. Their occupation was only occasional, at such times when the Egyptian state wanted to organise naval expeditions. Doubtlessly, these took place only every five or ten years. These operations were particularly difficult to organise. To be able to set sail from the coast, it was first necessary to cross the Eastern Desert transporting conifer-wood boats which they wanted to use there in disconnected pieces. Then it would have been necessary to reassemble them on the bank. To save themselves as much as possible from undertaking this arduous and delicate task, these boat fixtures were not brought back to the Nile Valley once the expedition was finished. They were left at the site, along with the rest of the material necessary for these expeditions, awaiting reuse, sometimes for several years. For this reason the most characteristic feature of these intermittently-used harbours is the presence, at short distance from the coast, of a system of storage galleries where these boats could be stored, once they had been dismantled again.

The site of Wadi el-Jarf is certainly the first-known experiment in this type of harbour management. The material assemblage discovered at the site over nine seasons of excavation (2011-2019) (including an abundant collection of inscriptions and texts), demonstrates clearly that it was occupied only very briefly during the reigns of the first two kings of the 4th Dynasty: Snefru and Khufu (c. 2600-2500 BC). The choice of this location had been motivated by several favourable environmental factors, of which one of the most important was the presence of an abundant source of water, today enclosed within the monastery of Saint-Paul, about a dozen kilometres from the ancient settlement. This enabled the relatively numerous troops sent there on a mission to access water. On the coast, the harbour facilities themselves had been set up directly beside a gap in the coral reef which borders the coastline, which permitted safe passage to the shore. At this spot a massive jetty in the shape of an L was constructed. Oriented to the north, it measured 200 m from east to west and 200 m from north to south. It was intended to provide shelter for the boats against the wind and the currents, and it is certainly the most ancient remains of an artificial harbour developed in a maritime environment which have survived to this day. Close to the harbour, several buildings with small rooms were constructed in order to temporarily house the teams who had been sent on these missions. A collection of more than 100 anchors, which had been carefully stored, awaiting reuse, were unearthed there. Finally, an impressive system of storage galleries, comprising more than thirty cavities (whose length varies from 15 m to more than about 30 m) had been dug into good quality sandstone some 5 km from the coast, in the last outcrops of the Gebel Galala massif. It was during the excavation of this set of galleries, which had all been accorded an impressive system of closure consisting of great blocks of limestone, that copious amounts of material dating to the start of the 4th Dynasty, were regularly recovered. These included ceramic items, tools, seals and fragments of boats.

But the most remarkable discovery took place during the excavation season of 2013 with a highly significant collection of papyri which had been left at the entrance of one of the galleries. It contained various documents comprising both accounts and log books which belonged to one of the teams which stayed at the site at the end of the reign of Khufu. It was left there when this contingent departed, probably during the last significant occupation of the harbour. Hundreds of fragments, without doubt having originally belonged to about 30 separate rolls of papyrus, were discovered. They are, to this day, the most ancient written papyri known. The surprise was also to realise that an important part of this documentation concerned the construction site of the pyramid of Khufu at Giza, where the team to whom this documentation belonged, had worked for several months before being sent to the Red Sea coast. The “journal of Merer”, the daily report of a minor official who was indisputably an eye-witness to the building of this famed monument, brings valuable information about the transportation of construction materials which were destined for the Great Pyramid. The presence of this collection of archives at the site of Wadi el-Jarf is the only confirmation of the close link which existed between this harbour and Khufu’s site at Giza. Without doubt, through this harbour the necessary copper for use by the monument’s builders was procured, after having been transported across the Gulf of Suez at this latitude.

Pierre Tallet (Sorbonne University, UMR 8167)

يقع موقع وادي اﻟﭼَرْف على ساحل خليج السويس، إلى الجنوب قليلًا من مخرَج المَمَرِّ الكبيرِ لوادي عَرَبَة الذي يربط وادي النيل بالبحر الأحمر عند خط عرض الفيوم. فهو، مع عين السُّخْنة ومَرْسَى جواسيس، أحد الموانئ الثلاثة المؤقتة في العصر الفِرْعَوْنيّ والتي تم تحديدها مؤخرًا على هذا الخط الساحليّ.

وقد تمَّت تهيئة جميع هذه الإنشاءات لتسهيل الوصول، عن طريق البحر، سواء إلى جنوب شبه جزيرة سيناء (حيث نشاط المصريين في مناجم النحاس والفيروز)، أم إلى الأبعد مكانًا، بلاد بونت، في منطقة باب المَنْدَب. لم يتم إشغال هذه المباني إلَّا من حينٍ لآخر، عندما كانت الدولةُ المصريَّةُ ترغب في تجهيز الحملات البَحْريَّة، والتي كانت تتمُّ على الأرجح كل خمس أو عشر سنوات. كانت هذه العمليَّات صعبة الإعداد بصفة خاصة: فحتى يكونَ الفرد قادرًا على السفر من الساحل، كان من الضروريّ أولًا عبور الصحراء الشرقيَّة، مع نقل القِطَع المُفكَّكة للقوارب من خشب الصَّنَوْبَر التي يريدُ الفردُ استخدامها هناك، والتي كان ولا بُدَّ من إعادةِ تجميعها على الشاطئ. وللتغلُّب على أكبرِ جزءٍ ممكنٍ من هذه العمليَّة المُضْنيَة والمعقدة، فإن أجزاءَ هذه القوارب لم تكن تعودُ إلى وادي النيل بمجردِ انتهاءِ الرحلة. فقد كانوا يتركونها في الموقع، مع بقيَّةِ المستلزمات اللازمة لهذه الحملات، أحيانًا لعدة سنوات، في انتظار إعادة استخدامها. ولهذا السبب، فإن أهمَّ سمةٍ لهذه الموانئ المؤقتة هي وجودُ نظامٍ من أرْوِقَة المخازن على مسافةٍ قصيرةٍ من الساحل، والتي يمكن إيداعُ هذه القوارب فيها بعد تفكيكها مرةً أخرى.

إن موقع وادي اﻟﭼَرْف هو بالتأكيد أوَّلُ تجريبٍ لهذا النوع من تجهيز الموانئ، ومجموعةَ المواد التي اكتُشفت في الموقع بعد نهاية تسعِ بعثاتِ تنقيب (٢٠١١-٢٠١٩)؛ وعلى الأخص مجموعةٌ وفيرةٌ للغاية من النقوش والنصوص، توضح بالفعل أنه لم يتم إشغالُه إلَّا لفترةٍ وجيزةٍ فقط في عهد أول وثاني ملوك الأسرة الرابعة سنفرو وخوفو (قرابة ٢٦٠٠-٢٥٠٠ ق. م.). كان الدافع وراء اختيار هذا الموقع هو وجود عدة عوامل مواتية؛ من أهمها على الإطلاق وجودُ مصدرٍ وفيرٍ للمياه داخل حدود دير الأنبا بولا حاليًّا على بعد نحو عشرةِ كيلومتراتٍ من الإنشاءات القديمة؛ مما سهَّل إمكانيَّة توفير المياه لأعداد القوات الكثيرة نسبيًّا التي كان يتم إرسالُها إلى هناك. أما على الساحل، فقد تم تجهيزُ إنشاءاتِ الميناء نفسها، عموديَّةً على أخدودٍ من الشِّعاب المَرْجانيَّة الموجودة على طول الساحل؛ مما يوفر الوصول الآمن إلى الشاطئ. كما تم بناءُ رصيفٍ ضخمٍ على شكل حرف L بوجهة شمالية، يبلغ طولُه ٢٠٠ متر من الشرق إلى الغرب، و٢٠٠ متر من الشمال إلى الجنوب. كان الهدف منه توفيرَ مأوىً للقوارب من الرياح والتيارات، وهو بلا شك يمثل اليوم أقدمَ بقايا ميناءٍ اصطناعيٍّ تمَّت تهيئتُه في البيئة البَحْريَّة. وبالقرب من الميناء، تم أيضًا بناء العديد من المباني بغرف فرديَّة للإقامة المُؤقَّتة للفرَق التي كان يتم إرسالُها في مهمة. كما تم الكشفُ عن مجموعةٍ تضم أكثر من ١٠٠ مِرْسَاةً للقوارب التي أُودعت بعنايةٍ انتظارًا لإعادة استخدامها. وأخيرًا، تم تجهيزُ نظامٍ مذهلٍ من أروقة المخازن، يضمُّ أكثرَ من ثلاثين تجويفًا (يتراوح امتدادُها ما بين ١٥ مترًا وأكثر من ثلاثين مترًا) من الحجر الجيري ذي نوعية جيدة، وذلك في السُّفوح الأخيرة للكتلة الجَبليَّة لجبل الجلالة، على بُعد قرابةِ ٥ كيلومتراتٍ من الساحل. وبفضل التنقيب في هذه المجموعة من الأروقة، والمُزوَّدة جميعُها بنظامِ إغلاقٍ فعَّال يتكوَّن من كتلٍ كبيرةٍ من الحجر الجيريّ، تم بانتظامٍ جمعُ موادَّ وفيرةٍ للغاية يرجع تاريخُها إلى أوائل الأسرة الرابعة (خَزَفْ، أدوات، أختام، أجزاء من قارب). لكن الاكتشافَ الأبرزَ كان خلال بعثة التنقيب ٢٠١٣ لمجموعة مهمة جدًّا من البَرْديَّات التي تُركت عند مدخل أحد هذه الأروقة، وهي مستندات مُتنوِّعة، بما في ذلك حسابات وسِجلَّات يوميَّة، تخصُّ إحدى الفرَق التي تردَّدت على الموقع في نهاية عهد خوفو، ولكن تم التخلِّي عنها وقت مغادرةِ هذه الفِرْقَة، ربما خلال آخر إشغال فِعْليّ للميناء. كما تم الكشفُ عن مئات الأجزاء، التي كانت دونَ شَكٍّ تنتمي في الأصلِ إلى قرابة ثلاثين بَرْديَّةً مختلفة، والتي تُعدُّ في الوقتِ الحاليِّ من أقدم البَرْديَّات المُسجَّلة المعروفة. وكانت المفاجأةُ هي أن نلاحظَ أن جُزءًا مهمًّا من هذا التوثيق كان في الواقع يتعلَّقُ بالعملِ في موقعِ بناءِ هرمِ خوفو في الجيزة حيث عمل الفريقُ الذي يمتلك هذا التوثيقَ قبل بضعةِ أشهرٍ من إرساله إلى ساحل البحر الأحمر. «يوميَّات ميرير»، هي تقريرٌ يوميٌّ من موظَّفٍ صغير يُعدُّ بلا منازع شاهدَ عيانٍ على بناءِ هذا الأثرِ التاريخيّ، ويوفِّر بالتالي معلوماتٍ قيِّمةً عن وسائل نقلِ موادِّ البناءِ المُخصَّصة للهرمِ الأكبر. إن مجرَّدَ وجودِ هذه المجموعةِ من المحفوظاتِ في موقع وادي اﻟﭼَرْف، يؤكِّد كذلك الارتباطَ الوثيقَ بين تجهيز هذا المرْفَأ وموقع خوفو في الجيزة؛ حيث أتاح الميناءُ، في النهاية، بعد عبورِ خليجِ السًّويْس عند خط العرض نفسه، توفيرَ النُّحاسِ اللازمِ لتصنيعِ الأدواتِ اللازمة لبُنَاةِ الأهرام.

پيير تاليه (جامعة السُّوربُون، UMR 8167)

Bibliographie

- P. Tallet, G. Marouard, D. Laisney, « Un port de la IVe dynastie au ouadi el-Jarf (Mer Rouge) », BIFAO 112, 2012, p. 399-346, en ligne, https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/112/24/.

- P. Tallet, « Les ports intermittents de la mer Rouge à l’époque pharaonique. Caractéristiques et chronologie », Nehet 3, 2015, p. 31-72.

- P. Tallet, G. Marouard, « The Harbor facilities of King Khufu on the Red sea shore: The Wadi el-Jarf/El-Markha system », JARCE 52, 2016, p. 135-177.

- P. Tallet, Les papyrus de la mer Rouge. I. Le « journal de Merer » (papyrus Jarf A et B), MIFAO 136, Le Caire, 2017.

- P. Tallet, Les papyrus de la mer Rouge. II. Le « journal de Dedi » et autres fragments de journaux de bord (papyrus Jarf C, D, E, F), MIFAO, Le Caire, sous presse.