Ouadi Sannour

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.c463-7ac9 |

IdRef IdRef | 260086150 |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 2014 |

Les exploitations de silex du Ouadi Sannur (Galâlâ nord)Opération de terrain 17133

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie

🔗 Labex Structuration des mondes sociaux SMS (SMS)

Cofinancements

🔗 Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie

🔗 Labex Structuration des mondes sociaux SMS (SMS)

Dates des travaux

février - mars

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2022 : 10.4000/baefe.8215

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.5934

2020 : 10.4000/baefe.2744

2019 : 10.4000/baefe.955

Participants en 2024

Cadre géographique

Le Gebel el-Galala el-Baharia forme un grand plateau calcaire situé au nord du Ouadi Araba, entre vallée du Nil et mer Rouge. Ce plateau, qui déclive vers le sud-ouest, est parcouru d’un vaste réseau de ouadis qui empruntent parfois des canyons peu profonds débouchant sur de vastes vallées sèches en direction de la vallée du Nil. C’est le cas du Ouadi Sannour et du Ouadi Abou Rimth qui se développent vers le sud, et du Ouadi Warag qui s’écoule en direction du nord-ouest. Le vaste complexe de mines est localisé dans la partie amont de ces réseaux hydrographiques, là où les calcaires de l’Éocène, contenant de riches formations de silex, ont été entaillés à différents degrés. L’excellente qualité de ces matériaux a suscité l’intérêt des artisans de la taille du silex égyptiens qui ont produit des dizaines de milliers d’outils destinés aux centres consommateurs de la vallée du Nil.

Historique des recherches

Entre 1876 et 1885, le botaniste allemand Georg August Schweinfurth découvre, dans deux localités du Galala-nord – le Ouadi Sannour et le Ouadi Warag –, des concentrations d’éclats et de nucléus en silex qu’il interprète comme étant des ateliers de taille du silex. Ces découvertes prennent place vingt ans avant celles du Ouadi Sheikh par Heywood Walter Seton-Karr. En dépit d’une mention publiée dans la revue Science en 1885 et dans le Bulletin de l’Institut égyptien (BIE) en 1886, les découvertes du scientifique allemand, contrairement à celles du Ouadi Sheikh, sont restées dans le silence durant plus d’un siècle. En 2014, nous avons commencé des prospections sur le terrain et localisé avec succès les deux sites identifiés par G.A. Schweinfurth, restés complètement intacts depuis leur découverte environ 140 ans auparavant. Nous avons ensuite étendu la recherche sur un espace géographique plus large, en nous appuyant sur des indices tirés de l’examen approfondi des images satellites, et avons découvert de nombreux sites nouveaux répartis sur une superficie de plus de 600 km2. Ces observations ont été complétées par des fouilles localisées en différents points du Galala pour approfondir la nature des installations et leur chronologie.

Un vaste complexe minier

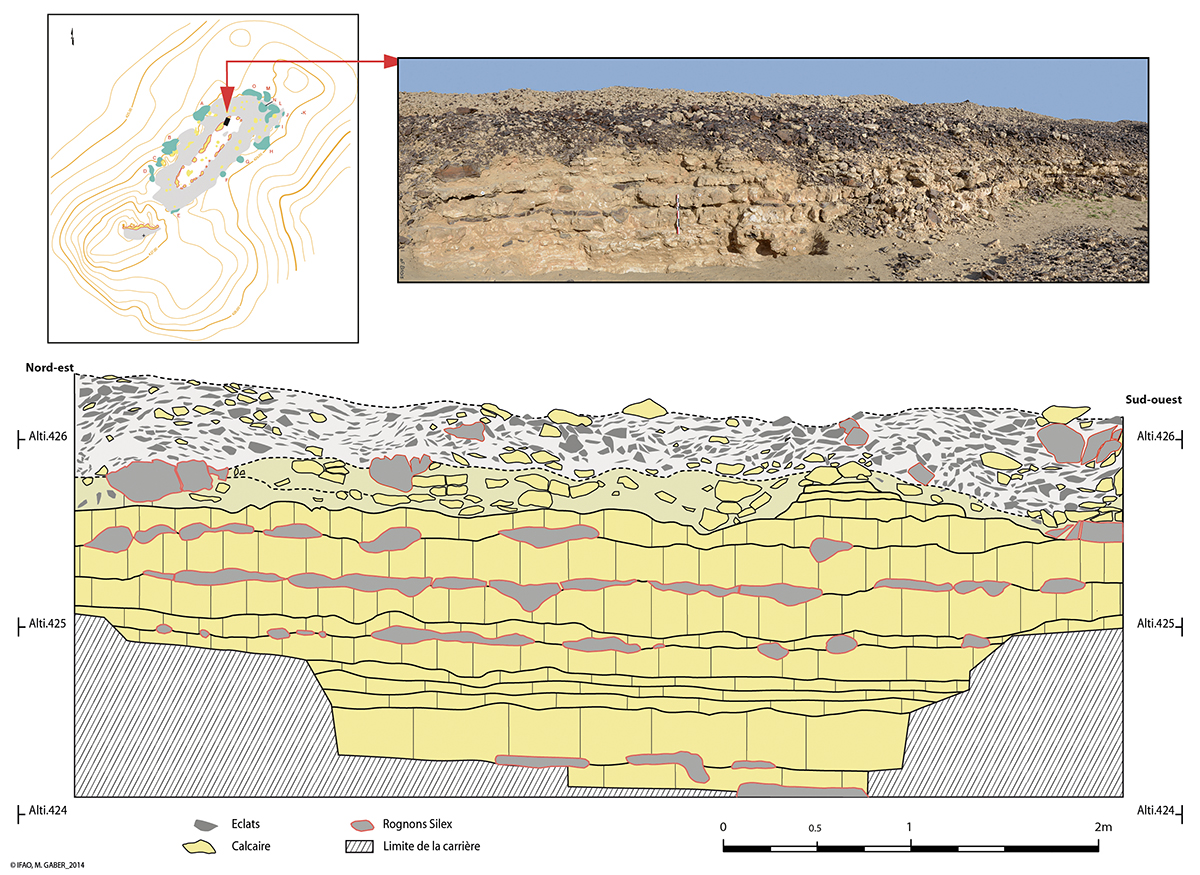

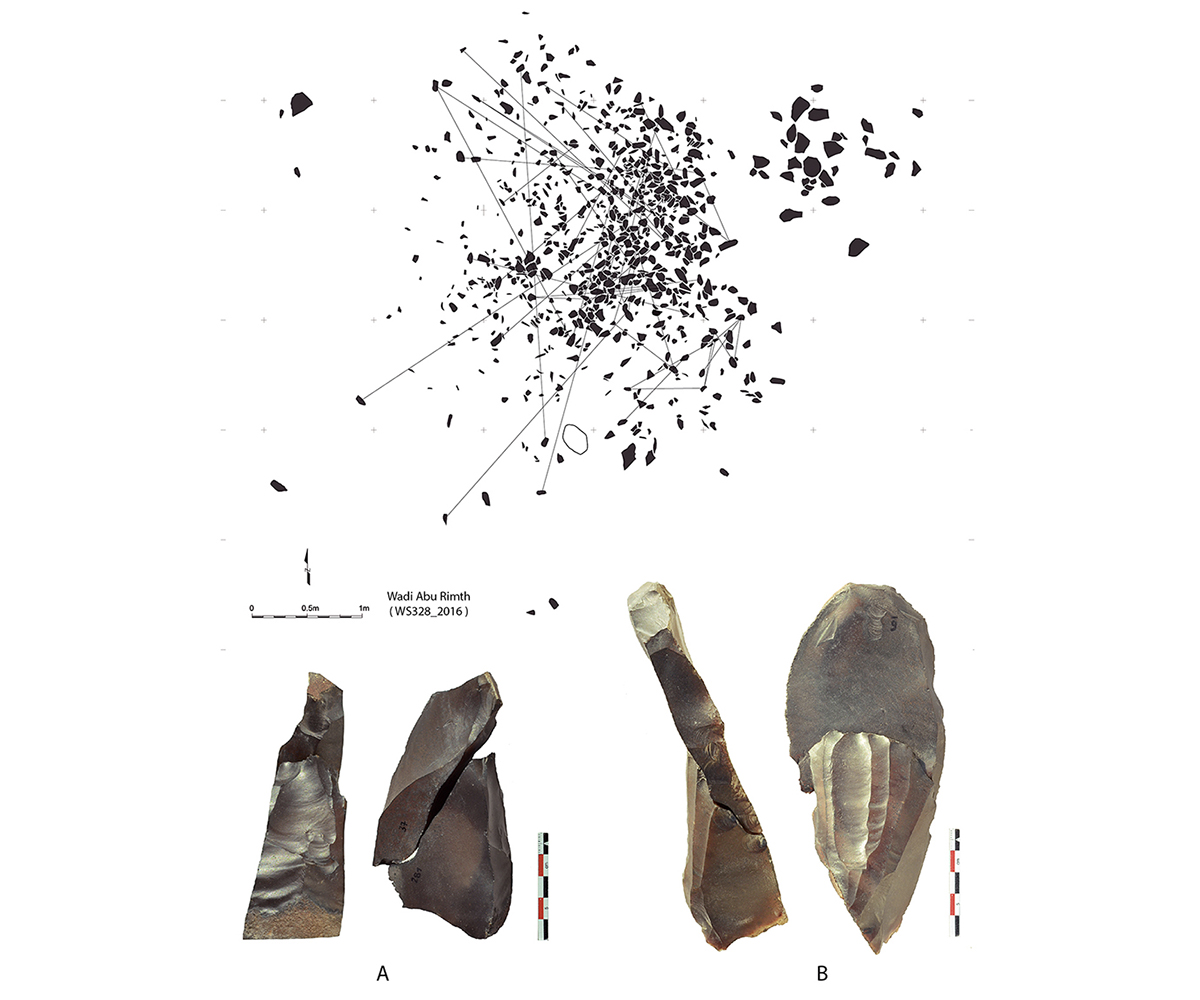

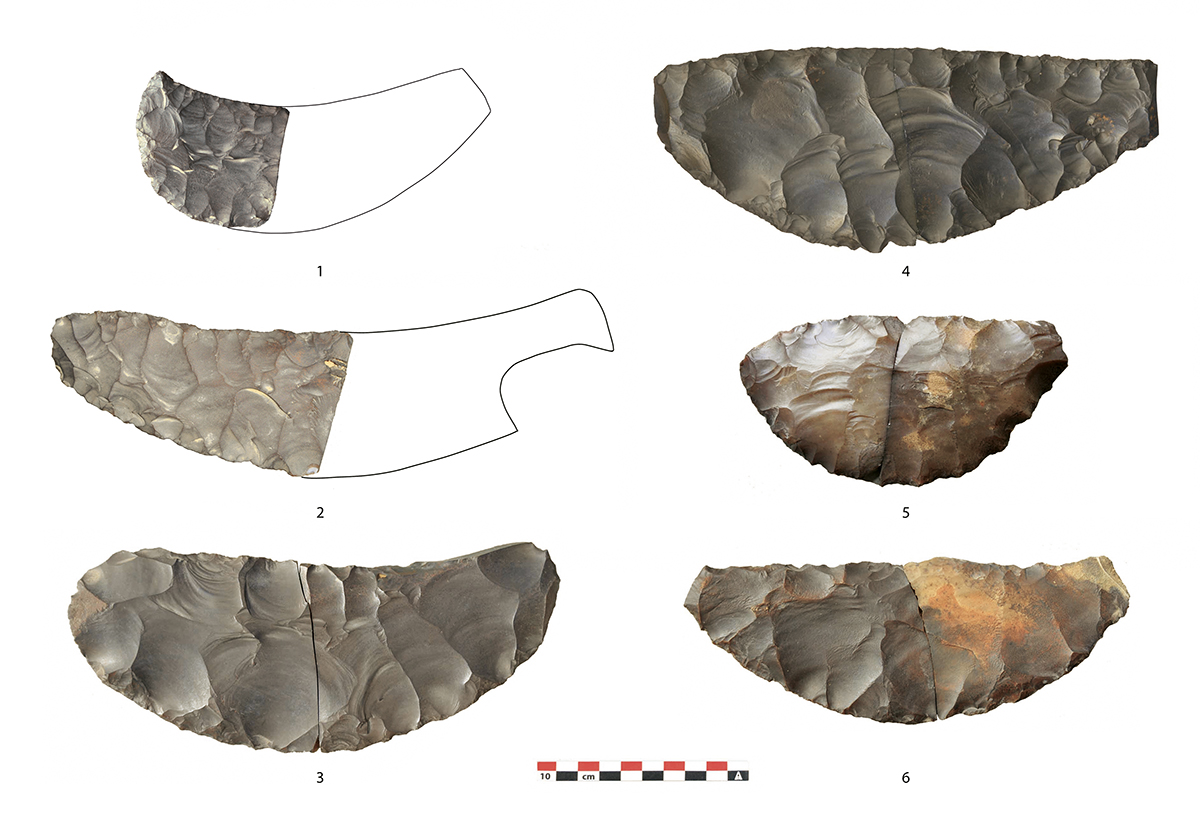

En suivant les pistes explorées par G.A. Schweinfurth, nous avons pu sortir de l’oubli les sites révélés dans le courant du xixe s. par le savant allemand, en mesurer l’importance, prolonger ses découvertes par de nouvelles investigations de terrain qui ont permis de mettre en lumière leur véritable portée. On sait à présent que la partie occidentale du Galala-nord possède de riches ressources en silex de grande qualité. Celles-ci ont donné lieu à des exploitations de type industriel qui, d’après les premiers éléments de datation dont nous disposons, s’échelonnent de la période protodynastique jusqu’à l’Ancien Empire. L’importante densité de sites miniers sur un territoire aussi vaste et l’exploitation de gîtes parfois très modestes et isolés indiquent que les mineurs ont exploré la région de manière systématique pour en extraire les meilleurs matériaux. L’important réseau de pistes qui traverse la partie occidentale du Galala a certainement favorisé cette très bonne connaissance des ressources. Les formations de silex étaient facilement repérées dans le paysage par la présence de niveaux altérés par la thermoclastie dessinant des bandes de teinte sombre sur le flanc des collines ou les bords des plateaux. L’activité minière était généralement conduite au moyen de longues tranchées creusées dans le substrat en suivant la disposition naturelle des strates calcaires où se trouvaient les meilleurs blocs de silex. Des puits étaient également parfois creusés sur les replats pour atteindre les bancs de silex en place accessibles à faible profondeur. Les haldes de ces mines encore visibles forment des monticules de cailloux calcaires bordant les excavations.

François Briois (EHESS/UMR 5608) et Béatrix Midant-Reynes (CNRS, UMR 5608)

Geographic framework

Gebel el-Galala el-Bahariya is a great limestone plateau situated to the north of Wadi Araba between the Nile and the Red Sea. This plateau, which slopes down to the south-west, is crossed by a vast network of wadis, sometimes incorporating shallow canyons which open out into huge dry valleys towards the Nile Valley. While Wadi Sannur and Wadi Abu Rimth head towards the south, Wadi Warag runs in a north-westerly direction. The huge complex of mines is situated in an area uphill from these hydrographic networks, where Eocene limestone containing rich formations of flint has been quarried to varying degrees. The excellent quality of this raw-material has attracted the interest of Egyptian artisans of flint who produced tens of thousands of tools which were destined for consumer centres in the Nile Valley.

Research History

Between 1876 and 1885, in two locations in northern Galala (Wadi Sannur and Wadi Warag), the German botanist Georg August Schweinfurth discovered concentrations of flint blades and cores which he interpreted as sizeable workshops of flint. These discoveries took place twenty years before those by Henri Walter Seton-Karr at Wadi Sheikh. Despite a mention of it being published in the journal Science in 1885 and in the Bulletin de l’Institut égyptien (BIE) in 1886, the discoveries of the German scholar, contrary to those at Wadi Sheikh, remained unnoticed for more than a century.

In 2014 we began surveys in the region and successfully pinpointed the two sites identified by G.A. Schweinfurth, which had remained completely intact since their discovery about 140 years previously. We then extended exploration over a wider geographical region whose extent was determined on the basis of features identified during the close examination of satellite images, and having discovered numerous new sites spread over a surface area of more than 600 km2. These observations have been complemented by localised excavations at different places in the Galala so as to gain further understanding of the installations and their chronology.

A vast mining complex

Following the tracks explored by G.A. Schweinfurth, we have been able to bring back from obscurity those sites revealed during the 19th century by the German scholar, to determine their importance. His discoveries have been enhanced through new field investigations which have thrown light on their true significance. The western part of the northern Galala is currently known to possess rich resources in fine quality flint. These led to exploitation on an industrial scale which, according to the first dating information at our disposal, extends from the Proto-dynastic period to the Old Kingdom.

The significant density of mining sites in a region so vast and the exploitations of flint sources which are often very modest and isolated, indicates that the miners explored the area in a systematic manner in order to extract the best-quality raw materials. The important trail network which crosses the western part of the Galala certainly helped in the identification of resources. Flint formations were easily located in the landscape by the presence of bands of rock on the flank of hills or on the edges of the plateaux which had been altered by thermal weathering and became dark in colour. Generally speaking, mining activity was conducted in the middle of long trenches dug into the substrate which followed the natural deposition of limestone strata where the best blocks of flint were to be found. Pits were also sometimes dug on ledges to reach layers of flint accessible at shallow depth. The still visible dumps of these mines form mounds of limestone boulders on the edge of the excavations.

François Briois (EHESS, UMR 5608) and Béatrix Midant-Reynes (CNRS, UMR 5608)

الإطارُ الجغرافيّ

يُكوِّنُ جبلُ الجلالةِ البَحْريَّة هضبةً جيريَّةً كبيرة تقعُ شمال وادي عَرَبَة، بين وادي النيل والبحر الأحمر. هذه الهضبةُ التي تميلُ باتجاه الجنوب الغربيّ تخترقُها شبكةٌ واسعةٌ من الوديانِ تمرُّ في بعضِ الأحيانِ بمضايقَ ضحلة العمق، تؤدِّي إلى وديانٍ جافةٍ واسعة، باتجاه وادي النيل. هذا هو الحالُ بالنسبة إلى وادي سَنُّور، ووادي «أبو رمث» اللذين يتقدمان نحوَ الجنوب، ووادي وراج الذي يجري في اتجاهِ الشمالِ الغربيّ. يقعُ مُجمَّعُ المناجمِ الشاسعِ في الجزءِ العُلْويّ لهذه الشبكةِ من المُسطَّحات المائيَّة؛ حيث الأحجارُ الجيريَّةُ التي تعودُ للعصر الإيوسينيّ والتي تحوي تكويناتٍ ثريَّةً من الظِّرَّان، احتُزَّت بدرجاتٍ متفاوتة. الجودةُ العاليةُ لهذه المواد أثارت اهتمامَ حِرَفيِّي تقطيع الظِّرَّان المصريين الذين أنتجوا عشراتِ الآلافِ من الأدواتِ المُوجَّهة لمراكزِ الاستهلاكِ في وادي النيل.

التسلسلُ التاريخيُّ للأبحاث

في الفترة ما بين عامَيّْ 1876 و1885، اكتشف عالم النباتات جيورج أوجوست شڤاينفورت، في موضعين بالجلالة الشماليَّة في وادي سَنُّور، ووادي وراج، تركيزاتٍ كبيرةً من شظايا ونَوَى الظِّرَّان، وفسَّرها أنها ورش تقطيع الظِّرَّان. هذا الاكتشاف جاء قبل 20 سنة من اكتشافات وادي الشيخ، على يد هيوود والتر سيتون-كار. وبالرغمِ من وجود إشارةٍ منشورةٍ في مجلة (العلوم) و(حوليَّات المعهد المصري) في 1886، فإن اكتشافات العالِم الألمانىّ طواها الصمتُ لأكثرَ من قرنٍ من الزمان على عكس اكتشافات وادي الشيخ.

وفي 2014، بدأنا الاستكشافات الميدانيَّة، وحدَّدنا بنجاحٍ مكان الموقعيْن اللذيْن كان شڤاينفورت قد تعرَّف إليهما واللذيْن ظلَّا على حالتهما دون أدنى تغييرٍ منذ اكتشافهما قبل قرابة 140عامًا. ثم امتدت أبحاثُنا إلى مساحةٍ جغرافيَّةٍ أوسع، مستندين إلى مُؤشِّراتٍ استخلصناها من الفحص المُتعمِّق لصور الأقمار الصناعيَّة. واكتشفنا عدَّةَ مواقعَ جديدةٍ موزعة على مساحة أكثر من 600 كم2، واستكملنا هذه الملاحظات بأعمالِ تنقيبٍ في نقاطٍ مختلفةٍ من الجلالة لتعميقِ معلوماتنا عن طبيعةِ المنشآت، وتسلسلها الزمنيّ.

مُجمَّع مناجم شاسع

بعد أن تتبعنا الدروبَ التي استكشفها شڤاينفورت، استطعنا إخراجَ المواقعِ التي تمَّ رفعُها خلال القرن التاسع عشر على يدِ العالِم الألمانيّ من طيِّ النسيان، وقياس أهميَّتها وتعميق هذه الاكتشافاتِ بإجراءِ استقصاءاتٍ ميدانيَّةٍ جديدةٍ سمحت بالكشفِ عن أهميَّتها الحقيقيَّة. وفي الوقت الحالي، أصبحنا نعلم أن الجزءَ الغربيَّ من الجلالة الشماليَّة يحوي موارد غنيَّة من الظران ذي الجودة العالية، وهو ما فتح المجالَ لاستغلالها صناعيًّا. هذا الاستغلال - وفقًا للعناصر الأوليَّة للتأريخ التي بين أيدينا - يغطي الفترةَ من عصر ما قبل الأسرات حتى الدولة القديمة.

وتشير الكثافةُ العاليةُ للمواقع المَنْجميَّة على أراضٍ بهذا الاتساع، وإشغال أماكن سكنيَّة أحيانًا شديدة التواضع ومتفرقة، إلى أن عمالَ المناجمِ ارتادوا المنطقةَ بشكلٍ منتظمٍ لإستخراج أفضل المواد منها. ومن المؤكَّد أن شبكةَ الدُّرُوب التي تعبُر الجزءَ الغربيّ من الجلالة يسَّرت المعرفة الجيدة للموارد، فكان من الممكن تحديدُ أماكن تكوينات الظَّران بفضل التفجُّر الصخريّ الحراريّ والذي رسمَ شرائطَ دَكْناءَ اللون على جانبِ التلالِ أو أطرافِ الهضاب. والنشاطُ المنجميُّ كان يتمُّ عن طريقِ خنادقَ طويلةٍ حُفرت في الطبقات التحتيَّة، متبعةً الترتيبَ الطبيعيَّ لطبقاتِ الجير التي تحوي أفضلَ كُتَل الظِّرَّان. وكان يتمُّ أحيانًا حفرُ الآبارِ على جوانبِ التلِّ للوصولِ إلى منَصَّاتِ الظِّرَّان الموجودةِ على عمقٍ ضحل. وتُشكِّلُ أسطحُ هذه المناجمِ التي لا تزالُ ظاهرةً تلالًا من الحصى الجيريّ تحفُّ التجويفات.

فرانسوا بريوا (مدرسة الدراسات العليا للعلوم الاجتماعيَّة - UMR 5608)، وبياتريكس ميدان-رين (المركز الوطنيّ للبحث العلميّ - UMR 5608)

Bibliographie

- G.A. Schweinfurth, « Notes and News », Science 6/131, 1885, p. 116-120, en ligne, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1761562.

- G.A. Schweinfurth, « Les ateliers des outils en silex dans le désert oriental de l’Égypte », BIE 2/6, 1885-1886, p. 229-238.

- F. Briois, B. Midant-Reynes, « Sur les traces de Georg August Schweinfurth. Les sites d’exploitation du silex d’époque pharaonique dans le massif du Galâlâ nord (désert Oriental) », BIFAO 114/1, 2014, p. 73-98, en ligne, https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/114/03/.

- C. Köhler, E. Hart, M. Klaunzer, « Wadi el-Sheikh: A new archaeological investigation of ancient Egyptian chert mines », PLoS ONE 12(2): e0170840, 2017, p. 1-38, en ligne, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170840.

- F. Briois, B. Midant-Reynes, « A recent discovery: the flint mines of north Galala », EgArch 54, 2019, p. 27-31.