Dendara

| Noms anciens | tȝ Jnw.t tȝ nṯr.t , Tentyris |

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.271f-93e5 |

IdRef IdRef | 02722483X |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 1966 |

Dendara, espaces et développements d’une métropole régionaleOpération de terrain 17141

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

Université de Namur

Cofinancements

Dates des travaux

octobre

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2022 : 10.4000/baefe.8314

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.6063

2019 : 10.4000/baefe.1185

Participants en 2026

Dendara : Relevés épigraphiques, photographiques et architecturaux. Études théologiques.Opération de terrain 17142

Dendara est incontournable au regard du patrimoine monumental des derniers grands temples égyptiens. Le sanctuaire majeur a été entrepris en juillet 54 av. J.-C., sous le règne de Ptolémée XII (80-58 et 55-51 av. J.-C.). Son programme n’a jamais été totalement achevé – à l’exemple du temple d’Horus à Edfou –, puisqu’il manque les dispositifs architecturaux précédant les espaces les plus sacrés d’un grand sanctuaire de cette époque, à savoir un pylône et une cour. Ces éléments sont restés à l’état de chantier au niveau des fondations, à l’exception de la partie arrière du mur péribole qui a été démantelée à une période secondaire, les autres composants – naos (au cœur duquel résidait la divinité) et pronaos – sont quasi intacts. Ils abritent l’agencement de plus d’une cinquantaine de pièces sur plusieurs niveaux.

Ce sanctuaire, dont les murs et les plafonds foisonnent de textes et figures, était dédié à la déesse Hathor, patronne de la ville. Divinité féminine, d’origine cosmique, elle peut aussi être représentée sous la forme d’une lionne, d’un faucon femelle, ou d’une vache. Dans le temple, ses attributs varient, mais elle est fréquemment coiffée de cornes en forme de lyre enserrant un disque solaire. Le visiteur moderne est accueilli, au niveau du pronaos, par sa représentation la plus emblématique dans l’architecture monumentale : la colonne sistre dont le chapiteau est à l’effigie d’un visage radieux de jeune femme pourvue d’oreilles de vache dépassant de sa perruque surmontée par une façade en forme de sistre, attribut associé à la déesse.

Dernier témoignage d’importance nationale à être construit, l’architecture du temple d’Hathor a profité de l’évolution d’un savoir multimillénaire tant sur la résistance des matériaux que sur la maîtrise et la composition géométrique de l’espace. Un tel édifice était au cœur de l’agglomération dont la divinité, Hathor, qualifiait le toponyme Héliopolis. Dendara s’appelait ainsi « Héliopolis de la Déesse », à distinguer de l’Héliopolis du Nord (l’actuel Ayn Chams dans la périphérie du Caire) et de l’Héliopolis du Sud (la ville d’Ermant, au sud de Louqsor).

La présence de l’Ifao sur le site de Dendara s’est inscrite dans une de ses entreprises majeures : la publication des inscriptions des temples de la période gréco-romaine. Sous la direction d’Émile Chassinat, une fonte hiéroglyphique complète fut créée au Caire pour imprimer et publier les textes couvrant les murs de ces sanctuaires remarquablement conservés. Entre 1892 et 1934, É. Chassinat publia 14 volumes sur le temple d’Edfou et initia la série de publication des textes des temples de Dendara. Son œuvre fut poursuivie par François Daumas, puis Sylvie Cauville. Serge Sauneron, directeur de l’Ifao de 1969 à 1976, publia également le temple d’Esna.

L’étude des textes et des décors ne peut cependant être suffisante pour comprendre la complexité de ces édifices religieux, ainsi que l’évolution de l’environnement dans lequel ils ont été construits, puis renouvelés dans la durée du monde pharaonique.

Les fouilles archéologiques s’étaient, jusqu’à très récemment, limitées à la nécropole et remontaient aux campagnes anciennes menées par William M. Flinders Petrie en 1898, puis par Clarence Stanley Fisher de 1915 à 1918. Ces premières investigations, très partiellement publiées, furent réalisées avec une moindre exigence de documentation scientifique qu’aujourd’hui. Elles ont laissé de vastes espaces inexplorés. Le dégagement du temple par les sebakhin a livré des découvertes fortuites, sans contexte stratigraphique. Parmi celles-ci, on citera les parois monolithiques en calcaire d’une chapelle de Montouhotep II, reprise par Mérenptah, exposée dans le grand hall central du Musée égyptien du Caire à Tahrir.

Quelques sources archéologiques montrent que la ville était déjà une capitale régionale sous Chéops à la IVe dynastie (env. 2575-2450 av. J.-C.). Au cœur d’une région connue pour ses implantations prédynastiques, entre Nagada et Abydos, l’agglomération existe depuis l’origine des pharaons. Des sondages, au sud et à l’ouest du temple principal, ont révélé une occupation datant de la période Nagada II (3400-3200 av. J.-C.). La fréquentation humaine de l’endroit est attestée à des périodes bien plus anciennes puisque le plus vieux squelette humain de la vallée du Nil, remontant au Paléolithique moyen (il y a plus de 50 000 ans), a été retrouvé à 2 km du sanctuaire principal (Taramsa Hill). Dendara comme centralité territoriale a perduré bien au-delà du temps des dieux pharaoniques, jusqu’à la période médiévale. Ainsi le visiteur peut observer d’importants vestiges d’une église à plan basilical qui, en première analyse, daterait du VIe s. Le site offre ainsi l’opportunité d’étudier plus de cinq millénaires de développement d’une métropole territoriale, de sa population et de son environnement.

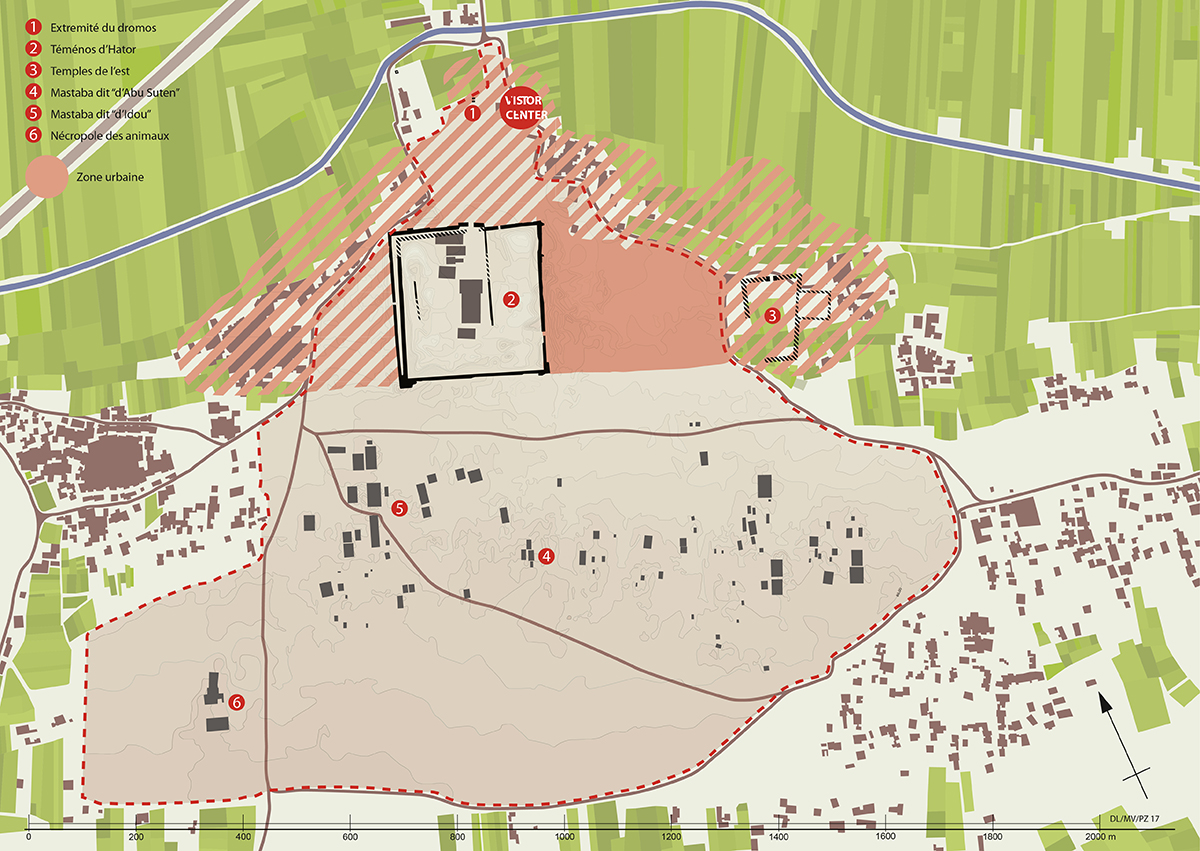

L’implantation de l’agglomération sur la frange désertique de la vallée du Nil la mettait à l’abri de la crue. Deux grands complexes religieux structuraient l’espace des zones d’habitat. Le premier (celui que l’on visite) abrite le sanctuaire de la divinité principale mais aussi des monuments complémentaires, bien conservés. Peu d’informations sont disponibles concernant le second domaine sacré, situé à plus de 400 m à l’ouest, dont la majeure partie correspond à des champs cultivés. Il était vraisemblablement consacré à la divinité appariée, Horus d’Edfou, mais n’a jamais été l’objet d’investigations. Ce domaine est identifiable par un magnifique portail monumental de la période romaine. Les murs de son téménos ont été arasés. Quelques blocs épars d’un sanctuaire annexe, en calcaire, subsistent.

Depuis les deux dernières décennies, l’Ifao a élargi ses investigations à l’étude architecturale des monuments ainsi qu’à l’exploration archéologique des quartiers d’habitations et des cimetières, développant des partenariats avec des institutions françaises et étrangères.

La reprise des travaux avec une approche moderne sur les divers aspects d’une métropole dans son environnement permettra d’établir une documentation précise et montre déjà un immense potentiel d’investigations inédites et de vastes secteurs inexplorés.

Pierre Zignani (CNRS, UMR 5060)

Dendara is incomparable with regard to the monumental heritage provided by the last great Egyptian temples. The principal temple was begun in July 54 BC during the reign of Ptolemy XII (80-58 BC and 55-51 BC). Its programme was never totally accomplished, following the example of the temple of Horus at Edfu, since it lacks architectural elements which precede the most sacred areas of a great temple of that period, namely a pylon and a court. These features occur at the site at foundational level, with the exception of the rear part of the peribolos wall which had been dismantled during another period. The other components, the naos (at the heart of which the divinity resided) and the pronaos, are almost intact. They comprise a layout of more than fifty rooms over several levels.

This temple, whose walls and ceilings abound with texts and images, was dedicated to the goddess Hathor, patron of the city. A feminine deity with cosmic origin, she can also be represented in the form of a lioness, a female falcon and a cow. In the temples her attributes vary, though she frequently bears lyre-shaped horns enclosing a solar disk. The modern visitor is greeted, at the pronaos level, by her most iconic representation in monumental architecture: the sistrum column with a capital which bears the image of the radiant face of a young woman adorned with cows’ ears which protrude over her wig. This is mounted on an architectural façade in the form of a sistrum, an attribute associated with the goddess.

The last testimony of national importance to be constructed, the architecture of the temple of Hathor has benefited from the evolution over many millennia of an understanding relating to the resistance of, as well as mastery of, construction materials, in addition to the excellence of the management of spatial design and geometry. Such a structure was at the heart of a regional metropolis, the name of whose divinity, Hathor, was appended to the toponym Heliopolis. Dendara was thus called “Heliopolis of the Goddess”, to distinguish it from Heliopolis of the North (modern-day Ain Shams on the periphery of Cairo) and the Heliopolis of the South (the city of Armant, south of Luxor).

IFAO’s focus at the site of Dendara comprises one of its major undertakings: the publication of the Graeco-Roman temple inscriptions. Under the direction of Émile Chassinat, a complete hieroglyphic font was created to print and publish the texts which cover the walls of these remarkably well-preserved temples. Between 1892 and 1934, É. Chassinat published 14 volumes regarding the temple of Edfu, then began the publication series relating to the texts in the temple of Dendara. His work was carried on by François Daumas, and then by Sylvie Cauville. Serge Sauneron, director of the IFAO from 1969 to 1976, similarly published the temple of Esna.

The study of texts and decoration could not, however, be sufficient for understanding the complexity of these religious buildings, in addition to the evolution of the environment in which they were constructed, then being modified throughout the Pharaonic period.

Archaeological excavations were, until very recently, limited to the necropolis, carrying on those earlier excavations which had been conducted by William M. Flinders Petrie in 1898, then, from 1915 to 1918, by Clarence Stanley Fisher. Clearance of the temple by the sebakhin led to fortuitous discoveries, but which lacked stratigraphic context. Among these are the monolithic limestone walls of a chapel of Montuhotep II, reused by Merenptah, which is exhibited in the great central hall of the Egyptian Museum of Cairo in Tahrir.

Some archaeological remains show that the city was already a regional capital under Khufu in the 4th century (c. 2757-2450 BC). At the heart of a region known for its predynastic sites between Naqada and Abydos, settlement has existed from the start of the Pharaonic era. Sondages to the south and west of the main temple revealed occupation dating to the Naqada II period (3400-3200 BC). Human visitation to the locality is also attested for much more ancient times since the most ancient human skeleton in the Nile Valley, belonging to the Middle Palaeolithic period (more than 50 000 years ago) was discovered at Taramsa Hill, 2 km from the main sanctuary. Dendara as a significant region continued well beyond the time of pharaonic gods up to the Medieval period. Thus, the visitor can observe important remains of a church with the plan of a basilica which, from first analysis, may date to the 6th century AD. The site therefore offers the chance to study more than five millennia of development of a provincial metropolis, its population and its environment.

The establishment of a settlement on the desert fringes of the Nile Valley sheltered it from the annual flood. Two great religious complexes delineate the residential areas. The first (the one which one can visit) includes the temple of the principal divinity, but also additional, well-preserved monuments. Little information is available concerning the second sacred area, situated more than 400 m to the west, which, for the most part, is now cultivated land. It was dedicated, probably, to the paired divinity, Horus of Edfu, but has never been the subject of investigation. This area is identifiable by a magnificent monumental gateway of the Roman period. Its temenos walls have been erased. Some scattered limestone blocks of a temple extension survive.

During the last two decades, developing partnerships with French and foreign institutions, the IFAO has broaden its investigations to include the architectural study of the monument as well as the archaeological excavation of residential quarters and cemeteries.

The resumption of work with a modern approach concerning the various aspects of a metropolis within its environment will enable precise documentation to be conducted. It is already revealing the immense potential of fresh investigations and of huge unexplored areas.

Pierre Zignani (CNRS, UMR 5060)

بالنظر إلى التراث الهائل لآخر المعابد القديمة المصريَّة الكبيرة، فإن دراسة معبد دَنْدَرَة حتميَّة لا مَفرَّ منها. تم البِدْءُ في بناء المعبد الرئيس في يوليو ٥٤ ق. م. في عهد بطليموس الثاني عشر (٨٠-٥٨ و٥٥-٥١ ق. م.). لم يكتمل أبدًا برنامجُه بالكامل - كما هو حال معبد حورس في إدفو؛ لأنه يفتقر إلى الخصائص المعماريَّة التي تسبق الأماكن الأكثر قداسةً بالنسبة إلى معبدٍ كبيرٍ في تلك الحقبة، وهي تحديدًا، الصرح والفناء. بقيت هذه العناصر على حالها في الموقع على مستوى الأساسات، باستثناء الجزء الخلفيّ من سور المعبد الذي تم تفكيكُه في فترة ثانويَّة. أما الأجزاء الأخرى - النَّاووس (حيث يقيم الإله داخلَه)، ومُقدِّمة المعبد - فهي سليمة تقريبًا. حيث تضمُّ أكثرَ من خمسين غرفةً تنتظم في عدَّة مستويات.

هذا المعبد، الذي تزخر جدرانُه وأسقفُه بالنصوص والأشكال، كان مُخصَّصًا للإلهة حتحور، ربَّة المدينة. فهي الألوهيَّة الأنثويَّة، من أصلٍ كونيّ، ويمكن تمثيلُها أيضًا على شكل لبؤة، أو أنثى الصقر، أو على شكل بقرة. وتختلف صفاتُها في المعبد، ويغطى رأسَها في كثيرٍ من الأحيان قرونٌ على شكلِ قيثارةٍ يتوسطها قرص الشمس. يتم استقبالُ الزائرِ الحديث، عند مقدمة المعبد، من خلال تمثيلها الأكثر رمزيَّةً في فن العمارة الضخمة: أعمدة الصلاصل حيث يأخذُ تاجُ العمودِ شكلَ وجهٍ مُشِعٍّ لامرأةٍ شابَّة مع أُذُنَيّْ بقرةٍ تتجاوزان شعرها المستعار، يعلوه واجهةٌ في شكلِ صلاصل، وهو رمزٌ مرتبطٌ بالإلهة.

يمثل المعبد آخر شهادة لبناءٍ ذي أهميَّة قوميَّة، حيث استفاد الفن المعماريّ لمعبد حتحور من تطوُّر معرفة آلاف السنين، سواء من ناحية قوة تحمُّل المواد المستخدمة أو من ناحية التمكُّن من معرفة التكوين الهندسيّ للمكان. تم تشييد هذا البناء وسط تجمُّعات السكان حيث تميز ألوهيةُ حتحور اسم هليوپوليس. وهكذا أُطلق على دَنْدَرَة «هليوپوليس الإلهة» لتمييزها عن هليوپوليس في الشمال (عين شمس الحالية في محيط القاهرة) وهليوپوليس في الجنوب (مدينة أرمنت، جنوب الأَقْصُر).

يندرج وجودُ المعهد الفرنسيّ للآثار الشرقيَّة في موقع دَنْدَرَة كجزءٍ من أحد التزاماته الرئيسة، وهو نشر نقوش معابد العصر اليونانيّ-الرومانيّ. تحت قيادة إميل شاسيناه، تمَّ سَبْك مجموعة حروف مطبعيَّة هيروغليفيَّة كاملة في القاهرة لطباعة ونشر النصوص التي تغطي جدرانَ مقاصير المعبد، والمحفوظة بشكلٍ مدهش. وفيما بين الأعوام ١٨٩٢ و١٩٣٤، قام شاسيناه بنشر ١٤ مُجلَّدًا عن معبد إدفو، ثم شرع في نشر سلسلة نصوص معابد دَنْدَرَة. وقد واصَلَ عمله فرانسوا دوما، ثم سيلڤي كوﭬيل. كما نشر سيرﭺ سوﻧرون (مدير المعهد من عام ١٩٦٩ إلى عام ١٩٧٦)، نصوصَ معبد إسنا.

ومع ذلك، فإن دراسةَ النصوصِ والزخارفِ لا يمكن أن تكون كافيةً لفهم مدى تعقيد هذه البنايات الدينيَّة؛ وكذلك تطور البيئة التي شُيِّدت فيها، ثم تجديدها بعد ذلك على طول العصر الفِرْعَونيّ.

كانت أعمال التنقيب الأثريّة حتى وقتٍ قريبٍ جدًّا مقتصرةً على الجبَّانة القديمة، وتعود إلى البعثات القديمة التي قادها ويليام م. فليندرز پتري في عام ١٨٩٨، ثم كلارنس ستانلي فيشر من عام ١٩١٥ إلى عام ١٩١٨. هذه الاستقصاءات الأوَّليَّة، التي نُشرت بشكلٍ جزئيٍّ جدًّا، تمَّت بأقل المتطلبات من التوثيق العلميّ مما هو عليه اليوم؛ فقد تمَّ تركُ مساحاتٍ شاسعةٍ غير مُكتشَفة. وأسفر إخلاء المعبد من قِبل السبَّاخين عن اكتشافاتٍ عَرَضيَّة، دون أي سياق طبقيّ، من بينها، نذكر الجدرانَ ذاتِ الكتلةِ الواحدةِ من الحجر الجيريّ للمعبدِ الصغيرِ الخاصِّ بمنتوحتب الثاني، والذي استولى عليه مرنبتاح، ويُعرض في القاعةِ المركزيَّةِ الكبيرةِ للمُتْحَف المصريّ في القاهرة بميدان التحرير.

تشير بعض المصادر الأثريَّة إلى أن المدينة كانت بالفعل عاصمةً إقليميَّةً إبَّان حكم خوفو من الأسرة الرابعة (قُرَابَة ٢٥٧٥-٢٤٥٠ ق. م.). وكانت تجمُّعات السكان قائمةً منذ نشأة الفراعنة في قلبِ منطقةٍ معروفةٍ بمستوطنات ما قبل الأسرات، في الفترة ما بين النَّقادة وأبيدوس. وكشفت المجسَّات التي تم إجراؤها جنوب وغرب المعبد الرئيس عن إشغالٍ يعودُ تاريخُه إلى فترة النَّقادة الثانية (٣٤٠٠-٣٢٠٠ ق. م.). ومن المؤكد أن ظاهرة الارتيادُ البشريّ للمكان قد تمت في فتراتٍ أقدمَ بكثيرٍ؛ حيث أن أقدم هيكل عظميّ بشريّ في وادي النيل، والذي يعود إلى العصر الحَجَريّ القديم الأوسط (منذ أكثر من ٥٠ ألف سنة)، تمَّ العثورُ عليه على مسافةِ كيلومترين من المعبد الرئيس (تل طرامسة). واستمرت دَنْدَرَة كمركزيَّةٍ إقليميَّةٍ إلى ما بعد وقت آلهة الفراعنة، وذلك حتى فترة العصور الوسطى. وهكذا يمكن للزائر ملاحظةُ بقايا مُهمَّة لكنيسةٍ ذاتِ تصميمٍ بازيليكيٍّ والتي، من واقع التحليل الأوَّل، يعود تاريخُها إلى القرن السادس. ويعطى الموقعُ بالتالي الفرصةَ لدراسةِ أكثرَ من خمسةِ آلافِ عامٍ من التطوُّر لمدينةٍ كبيرةٍ إقليميَّة ولسكانها وبيئتها.

كان توطين التكتُّل السكانيّ على أطراف صحراء وادي النيل من شأنه حمايتُها من الفيضان. هناك مجمعان دينيَّان كبيران يُحدِّدان حيِّز مناطق المساكن. يضمُّ الأول (وهو الذي نزوره) معبد الآلهة الرئيسة، ولكن أيضًا توجد آثار إضافية

محفوظة بشكل جيد. تتوافر القليلُ من المعلومات عن النطاق المُقدَّس الآخر، الواقع على بعد أكثر من ٤٠٠ متر، في الغرب؛ حيث يقترنُ الجزءُ الأكبرُ بالحقولِ الزراعيَّة. ومن المفترض أنه كان مُخصَّصًا للإله حورس معبود إدفو، لكن لم يتمَّ التحقُّق منه مطلقًا. يمكن التعرُّف على هذا النطاق من خلال بوَّابة أثريَّة رائعة من الفترة الرومانيَّة. وقد هُدِمَت جدرانُ الجَنَاح المُقدَّس الخاصة به ولا يزال هناك بعضُ الكُتَلِ من الحَجَر الجيريّ، تأتي من معبدٍ مُلحَق.

على مدى العقدين الماضيين، توسَّع المعهدُ الفرنسيُّ للآثار الشرقيَّة في المسح بهدف إنجاز الدراسات المعماريَّة للآثار؛ وكذلك الاستكشاف الأثريَ للأحياء السكنيَّة والمقابر، مع تطوير الشَّرَاكة مع المُؤسَّسات الفرنسيَّة والأجنبيَّة.

إن استئناف الأعمال بنَهْجٍ حديثٍ لمختلف جوانب مدينةٍ كبيرةٍ في بيئتها سوف يتيح إعداد توثيقاً دقيقاً، ويؤكِّد بالفعل الإمكانيَّة الهائلة لإجراءِ استقصاءاتٍ جديدةٍ وتحديد نطاقات واسعة غير مُستكشفَة.

پيير زينياني (معمارىّ، المركز الوطني للبحث العلمي، (UMR 5060

Bibliographie

- H.G. Fischer, Dendara in the Third Millennium B.C., New York, 1968.

- F. Daumas, Dendara et le temple d’Hathor, RAPH 29, Le Caire, 1969.

- P. Zignani, Le temple d’Hathor à Dendara. Relevés et étude architecturale, BiEtud 146, Le Caire, 2010.

- S. Cauville, M. Ibrahim Ali, Dendara. Itinéraire du visiteur, Leuven ; Paris ; Bristol, 2015.

- Y. Tristant, « Dendara in the Shadow of the Temple: Results of the New Excavations in the Necropolis (2014-2015) », BACE 26, 2016-2018, p. 79-90.

- Page web Dendara archivée (2017)