Karnak - sanctuaires osiriens

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.775c-4f49 |

IdRef IdRef | 259270776 |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 2000 |

Sanctuaires osiriens de KarnakOpération de terrain 17145

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

National Science Center of Poland

Cofinancements

🔗 Archéologie et patrimoine en Méditerranée (ARPAMED)

National Science Center of Poland

Dates des travaux

janvier - février

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2023 : 10.4000/11sxd

2022 : 10.4000/baefe.9294

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.5565

2020 : 10.4000/baefe.2950

2019 : 10.4000/baefe.1136

Participants en 2025

Histoire des fouilles

Au XIXe s., les premiers savants explorateurs, notamment Jean-François Champollion ou Karl Richard Lepsius, réalisèrent des relevés des chapelles qui étaient alors partiellement visibles, comme celle d’Osiris coptite. Anthony Charles Harris, Auguste Mariette, puis Georges Legrain entreprirent des dégagements qui amenèrent la mise au jour complète de certains sanctuaires ou la découverte d’édifices nouveaux comme celui consacré à Osiris « souverain de l’éternité ». Dans la deuxième moitié du XXe s., Henri Chevrier et Clément Robichon mirent au jour plusieurs constructions osiriennes, respectivement au nord-est de Karnak et dans le secteur de Karnak-nord, tandis que Jean Leclant, Paul Barguet et Claude Traunecker menèrent une série d’études qui éclairèrent la richesse des témoignages osiriens éparpillés dans Karnak. Dans les années 1990, l’étude des vestiges mis au jour par H. Chevrier et la poursuite des fouilles par François Leclère dans le secteur nord-est du temple amenèrent l’identification de plusieurs phases d’aménagement de la nécropole osirienne, depuis la fin du Nouvel Empire jusqu’à l’époque ptolémaïque. Des catacombes datant de Ptolémée IV, portant une riche décoration peinte, furent exhumées. À partir de 2000, le programme osirien a ouvert un nouveau champ d’activité sur les chapelles osiriennes longeant la voie dallée menant au temple de Ptah. Le chantier s’attache à l’analyse archéologique et l’édition épigraphique complète des trois chapelles bordant cette voie.

Les chapelles osiriennes et les divines adoratrices d’Amon

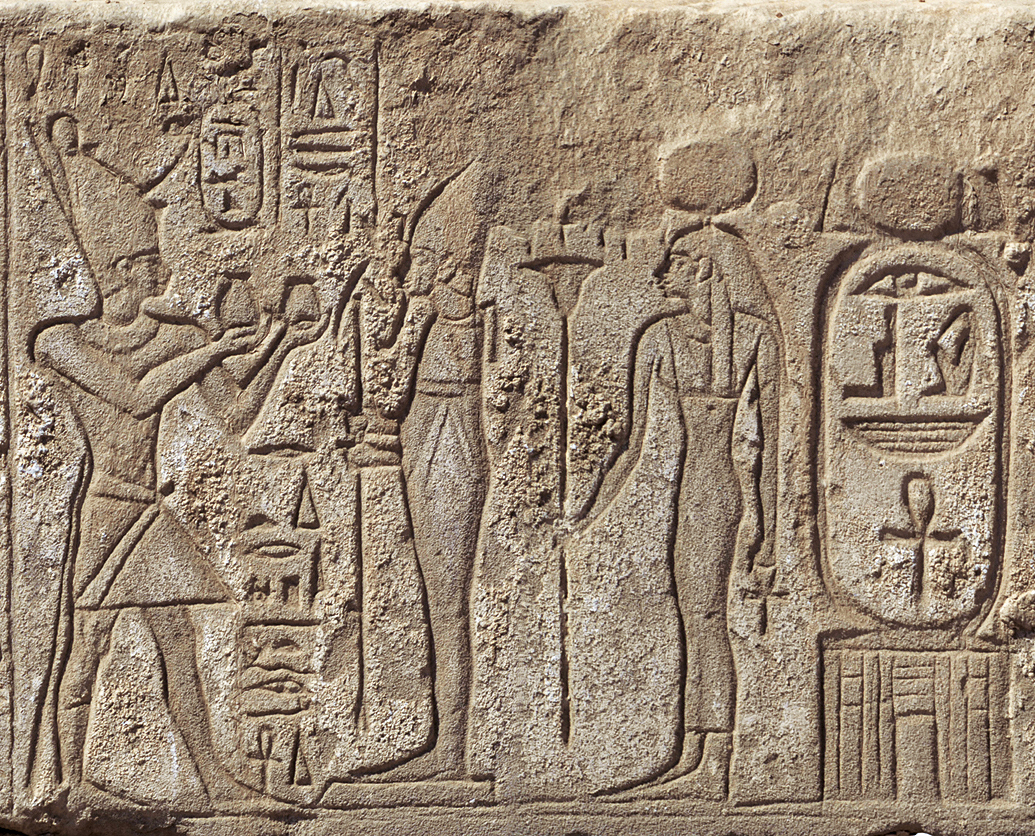

La plupart des chapelles osiriennes qui ont été édifiées autour des sanctuaires de Karnak l’ont été à l’initiative des divines adoratrices d’Amon, depuis le début de la Troisième Période intermédiaire jusqu’à la fin de l’époque saïte, au VIe s. av. J.-C. Leur localisation est révélatrice : elles se situent non seulement autour du cimetière osirien au nord-est du temple, mais aussi le long des voies processionnelles parcourant la partie nord du sanctuaire, en direction du quartier résidentiel des divines adoratrices et du harem d’Amon, sur le site du village moderne de Naga Malqata. Chaque chapelle met en scène le lien privilégié de ces princesses royales avec, d’une part, le dieu Amon, largement présent dans le programme décoratif, et d’autre part Osiris, à qui chaque chapelle voue un culte défini par une épithète spécifique : « maître de la vie », « celui qui inaugure l’arbre-iched », etc. Chaque chapelle s’inscrit dans un paysage osirien kaléidoscopique en présentant un programme théologique qui lui est propre. Celui qui caractérise la chapelle d’Osiris Ounnefer « maître des aliments » se distingue ainsi par sa coloration abydénienne qu’a privilégiée le majordome d’Ânkhnesneferibrê, Chéshonq, maître d’œuvre érudit de cet édifice. Ce dernier a été conçu comme un reposoir du fétiche processionnel d’Abydos, en empruntant une partie de son décor aux scènes des temples du Nouvel Empire situés dans cette illustre métropole osirienne.

Une vision diachronique de l’évolution du culte osirien dans son environnement

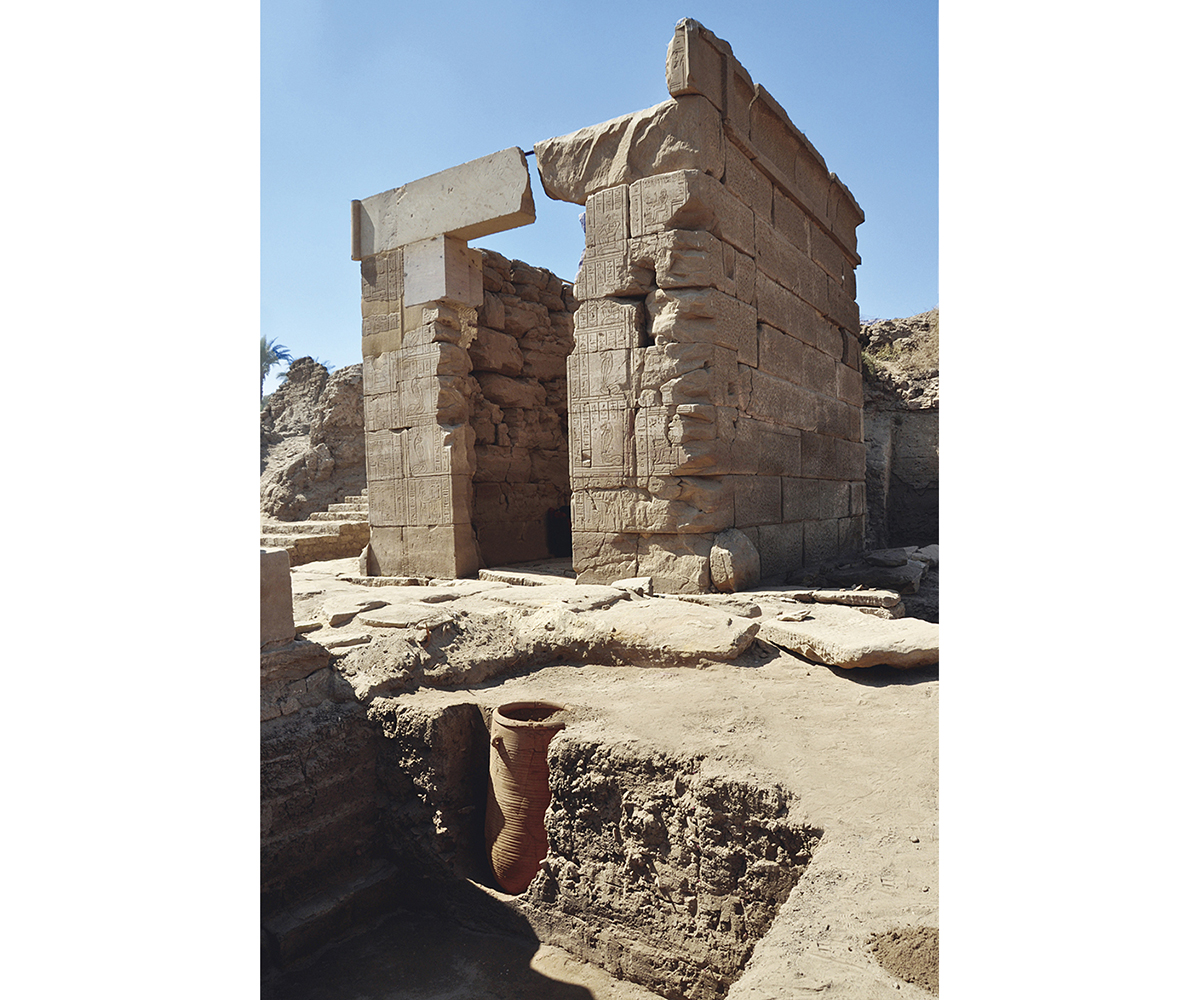

L’analyse archéologique s’est concentrée ces dernières années sur l’étude des trois chapelles édifiées, entre la XXVe et la XXVIe dynastie, à l’extérieur de la grande salle hypostyle, le long de la voie menant au temple de Ptah. Outre celle consacrée à Osiris Ounnefer Neb djefaou « maître des aliments », une plus ancienne est consacrée à Osiris Neb ânkh/pa oucheb iad « maître de la vie/celui qui secourt le malheureux », et une troisième, plus récente, à Osiris Ounnefer.

Ces chapelles ont été édifiées sur des niveaux datés entre la fin de la période ramesside et la Troisième Période intermédiaire, comprenant notamment d’imposants et larges massifs de briques crues, certains faisant partie de l’enceinte du domaine d’Amon, lors de la XXIe dynastie, avec de nombreuses estampilles au nom du grand prêtre Menkheperrê. D’autres vestiges révèlent la présence de cultes rendus avant l’édification des chapelles, comme certaines figurines, scellés et autre construction en briques crues. Mais l’élément le plus significatif est un dallage composé de larges dalles de grès et de calcaire, appartenant à un édifice antérieur à la chapelle d’Osiris Ounnefer Neb djefaou, potentiellement lié aux vestiges d’un édifice osirien antérieur. S’agissant des trois chapelles encore en place, le culte rendu à la divinité est bien plus aisé à appréhender à travers les différents programmes décoratifs présents sur ces trois chapelles que par l’analyse des niveaux archéologiques, car peu d’éléments en place ont pu être collectés pour alimenter la compréhension des espaces. Néanmoins la perception que nous avons des lieux a été éclairée par la découverte de plusieurs dépôts ; souvent constitués de figurines en bronze ou de vases en dépôt, ils sont associés à Osiris, qu’ils soient liés aux fondations des édifices ou aux rituels effectués postérieurement.

Les occupations ultérieures du secteur offrent de riches informations sur la permanence des lieux et des cultes. Malgré de nombreuses phases de destruction et de réoccupation entre le Ve et le IIIe s. av. J.-C., les édifices sont pour la plupart restaurés et insérés dans un cadre spatial plus large. Lors de certaines de ces phases, le culte rendu à Osiris semble perdurer, ce dont témoignent la restauration des monuments, la présence de figurines en bronze, de moules, et surtout quelques dépôts associant monnaies ptolémaïques et fragments de statues d’Osiris (uraeus, plumes d’autruche) qui ont pu être mis au jour au sein de certains réaménagements. Les phases ultérieures entre le IIe/Ier s. av. J.-C. et le Ier et le IIIe s. ap. J.-C., offrent encore une multitude d’informations, mais les nombreux remaniements du secteur ne laissent que de rares vestiges faisant écho aux cultes antérieurs.

Laurent Coulon (Ifao/EPHE-PSL) et Cyril Giorgi (Inrap)

Excavation history

In the 19th century the first explorer-scholars, notably Jean-François Champollion and Karl Richard Lepsius, undertook the documentation of chapels which were then only partially visible, such as the one of Osiris of Koptos. Anthony Charles Harris, Auguste Mariette, then Georges Legrain carried out clearing activities which led to the complete exposure of certain temples and the discovery of new structures, such as the one dedicated to Osiris “Sovereign of Eternity”. In the second half of the 20th century, Henri Chevrier and Clément Robichon unearthed several Osirian buildings to the north-east of Karnak and in the sector of Karnak-north respectively, whilst Jean Leclant, Paul Barguet and Claude Traunecker led a series of investigations which highlighted the richness of Osirian material remains scattered across Karnak. In the 1990s, the study of remains revealed by Henri Chevrier and the exploratory excavations of François Leclère in the north-east sector of the temple, led to the identification of several phases of development within the Osirian necropolis, extending from the end of the New Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. Catacombs dating to Ptolemy IV, with richly painted decoration, were revealed. From 2000 the Osirian programme opened a new area of activity involving the Osirian chapels along the paved way leading to the temple of Ptah. Archaeological analysis and the complete epigraphic publication of three chapels which border this way are in progress.

The Osirian Chapels and the Divine Adoratrices of Amun

The erection of most Osirian chapels around the temples of Karnak, dating from the start of the Third Intermediate Period to the end of the Saite era (the 6th century BC), was through the motivation of the Divine Adoratrices of Amun. Their locations are revealing. They are situated not only around the Osirian cemetery to the north-east of the temple, but also along the processional ways which run through the temple’s northern part in the direction of the residential quarter of the Divine Adoratrices and the Harem of Amun (now the site of the modern village of Naga Malqata). Each chapel displays the esteemed link of these royal princesses with, on the one hand, the god Amun (who is present to a noteworthy extent in the decorative programme), and on the other Osiris (to whom each chapel is dedicated with a cult defined by a specific epithet, e.g. “Lord of Life”, “One who inaugurates the ished-tree” etc.). Each chapel is inscribed with a specific Osirian decorum which presents a theological programme specific to itself. The one which features in the chapel of Osiris Wennefer “Lord of Food” is distinguished by its Abydenian colouring which Sheshonq, the high steward of Ankhnesneferibre and learned Master of Works for this structure, had conferred upon it. This last case had been treated as a repository for the processional fetish of Abydos, borrowing a part of its decoration from scenes in New Kingdom temples which are located in this illustrious Osirian metropolis.

A diachronic perspective on the evolution of the Osirian cult in its environment

In the last few years, archaeological analysis has been concentrated on the study of three chapels constructed outside the great Hypostyle Hall along the way leading to the temple of Ptah between the 25th and 26th Dynasties. Besides the one dedicated to Osiris Wennefer “Lord of food”, one more ancient is dedicated to Osiris Neb ankh/pa wesheb iad “Lord of Life/One who helps the unfortunate”, and a third, more recent, to Osiris Wennefer.

These chapels were constructed on levels dating between the end of the Ramesside period and the Third Intermediate Period, and comprise mainly imposing and large mud-brick walls, some of which form part of the enclosure of the Domain of Amun during the 21st Dynasty and bear numerous stamps with the name of the High Priest Menkheperre. Other remains reveal cultic activities which were conducted before the chapels were constructed, and included items such as figurines, seals and other mud-brick structures. But the most significant feature is a pavement consisting of large paving slabs of sandstone and limestone which belongs to a building dating before the chapel of Osiris Wennefer Neb djefau, and is potentially linked to the remains of a previous Osirian structure. With the three chapels still extant, the cult given to the divinity is much easier to understand through the different decorative programmes depicted in the three chapels than through analysis of the archaeological levels, but few elements in situ could be collected to aid our understanding of the areas. Nevertheless, our perception about these monuments has been augmented by the discovery of several hoards. Often comprising bronze figurines and vases, they are associated with Osiris and may be linked to the buildings’ foundations or to rituals conducted beforehand.

The subsequent occupation of the sector offers substantial information about the permanence of the places and the cults. Despite numerous phases of destruction and of reoccupation between the 5th and the 3rd centuries BC, the buildings are, for the most part, restored and set in a larger spatial context. During some of these phases, the cult given to Osiris seems to continue, which is attested by the restoration of the monuments, the presence of bronze figurines, moulds, and especially some hoards with Ptolemaic coins and fragments of statues of Osiris (uraeus and ostrich feathers) which could be part of some restoration work. The subsequent phases between 2nd/1st centuries BC and the 1st and 3rd century AD still offer a mass of information, but the numerous restorations in the sector have left only rare fragments which suggest echoes of previous cults.

Laurent Coulon (IFAO/EPHE-PSL) and Cyril Giorgi (INRA

تاريخ الحفائِر

في أوائل القرن التاسع عشر، قام المستكشفون؛ خاصة ﭼـان فرانسوا شامپوليون أو كارل ريكهارد لپسيوس، بإجراء عمليَّات رفع المقاصير التي كانت مرئيَّة جُزئيًّا آنذاك، مثل مقصورة أوزيريس القِفطيّ. ثم قام أنتوني تشارلز هاريس، وأوجوست مارييت، ثم ﭼورﭺ لوجران بالبدء في عمليَّات الإظهار التي أدت إلى الكشفِ الكاملِ عن بعضِ المقاصير الصغيرة، أو اكتشافِ مبانٍ جديدةِ مثل المبنى المُخصَّص لأوزيريس «سَيِّد الأبديَّة». وفي النصف الثاني من القرن العشرين، قام كُلٌّ من هنري شوڨرييه وكليمان روبيشون باكتشافِ عدَّة بناياتٍ أوزيريَّة، شمال شرق الكَرْنَك وفي قطاعِ شمالِ الكَرْنَك على التوالى، بينما قاد ﭼـان لوكلان، وپول بارجيه وكلود ترونيكر سلسلةً من الدراسات التي ألقت الضوءَ على غزارةِ الشواهد الأوزيريَّة المتناثرة في الكَرْنَك. وفي تسعينيَّات القرن الماضي، أدت دراسةُ الأطلال التي اكتشفها هنري شوڨرييه، واستمرارُ الحفائِر التي قام بها فرانسوا لوكلير في القطاع الشماليّ الشرقيّ من المعبد، إلى تحديدِ عدَّةِ مراحل من التنظيم المكاني في جَبَّانَة أوزيريس، منذ نهاية الدولة الحديثة حتى العصر البطلميَّ. كما تم الكشف عن مقابر تحملُ زخارفَ غنيَّةً بالألوان يرجعُ تاريخُها إلى عهد بطليموس الرابع. وبِدْءًا من عام ٢٠٠٠، فتح البرنامجُ الأوزيريُّ مجالًا جديدًا للعمل في المقاصير الأوزيريَّة على طول الطريق المُغَطَّى بالبلاط المُؤدِّي إلى معبد پتاح. ويركِّز موقعُ العملِ على التحليلِ الأثريِّ والنشرِ الكاملِ لكتاباتِ المقاصير الثلاثِ المُطِّلة على هذا الطريق.

المقاصير الأوزيريَّة والمُتعبِّدات الإلهيَّات لآمون

أُقيمت معظم المقاصير الأوزيريَّة حول المعابد الصغيرة في الكَرْنَك، والتي كانت فيما قبل خاصةً للمُتعبِّدات الإلهيَّات لآمون، منذُ بدايةِ عصر الانتقال الثالث إلى نهاية العصر الصَّاوي في القرن السادس ق. م. وموقعُ هذه المقاصير ذو دلالة، فهي لا تقعُ فقط حول المقابر الأوزيريَّة في الشمال الشرقيّ للمعبد، ولكن أيضًا على طول طرق المواكب عبرَ الجزءِ الشماليّ من قُدْسِ الأقداس باتجاه المنطقة التي تقطنُها المُتعبِّدات الإلهيَّات وحريم آمون، وذلك في موقع القرية الحديثة المُسمَّاة نجع ملقاطة. تصور كل مقصورة العلاقةَ المميزة لهؤلاء الأميرات الملكيَّات، من ناحية، بالإله آمون، والموجود على نطاقٍ واسعٍ في البرنامج الزخرفيّ؛ ومن ناحية أخرى بأوزيريس، حيث تُخصِّصُ كُلُّ مقصورةٍ عبادةً يتمُّ تحديدُها بصفةٍ مخصوصة؛ مثل «سَيِّد الحياة»، «الذي يفتتح الشجرة إشد»، إلخ. وتمثل كل مقصورة جزءًا من مشهد أوزيريّ يجمع بين مختلف الألوان، من خلال تقديمِ برنامجٍ لاهوتيٍّ خاصٍّ به. تتميزُ مقصورة أوزيريس ون نفر «سَيِّد الطعام» بتلوينها الأَبِيديّ (نسبةً إلى أبيدوس) الذي فضَّله شاشانق، رئيس خدم عنخنس نفر اب رع. وهو كذلك رئيسُ العمل المُحنَّك، الذي نفذ هذا البناء. وقد صُمم المبنى كمذبحٍ لتميمة موكب أبيدوس، مستعيرًا جزءًا من زخرفته من مشاهدِ معابدِ الدولةِ الحديثةِ الواقعةِ في هذه العاصمةِ الأوزيريَّةِ الشهيرة.

رؤية تأريخية لتطور العبادة الأوزيريَّة في بيئتها

ركَّز التحليلُ الأثرىُّ في السنوات الأخيرة على دراسة المقاصير الثلاث التي بُنيت فيما بين الأسرتين الخامسة والعشرين والسادسة والعشرين خارج بهو الأعمدة الكبير، وذلك على طول الطريق المُؤدِّي إلى معبد پتاح. بالإضافة إلى المقصورة المخصصة لأوزيريس ون نفر نب ﭼفـاو «سيد الطعام»، هناك مقصورةٌ أكثر قِدَمًا مخصصةٌ لأوزيريس نب عنخ/با وشب اياد «سيِّد الحياة/الذي ينقذ البائس»؛ أما الثالثة، والأحدث من بين هذه المقاصير، فهي مُخصَّصةٌ لأوزيريس ون نفر.

شُيِّدت هذه المقاصير على مستوياتٍ مؤرَّخةٍ فيما بين نهاية فترة الرعامسة وعصر الانتقال الثالث، وتضمُّ على الأخصِّ الكُتَلَ الكبيرةَ الضخمةَ من الطوب اللَّبِن، والتي يُشكِّل البعضُ منها جزءًا من سورِ منطقةِ آمون خلال الأسرة الحادية والعشرين، وكذلك الكثير من الأختام التي تحمل اسم كبير الكهنة (من خبر رع). هناك بقايا أخرى تكشف عن وجود طقوس تمَّت قبل بناء المقصورات؛ حيث أن بعض التماثيل الصغيرة مختومةٌ مع وجودِ بناءِ آخَرَ من الطوبِ اللَّبِن. ولكن العنصرَ الأكثر أهميةً هو وجودُ أرضٍ مبلَّطةٍ تتكون من ألواحٍ كبيرةٍ من الحجر الرمليّ والحجر الجيريّ، وهي تخصُّ بناءً سابقًا لمقصورة أوزيريس أون نفر نب ﭼفاو، ومن المحتمل أن تكونَ مرتبطةً ببقايا بناءٍ أوزيريٍّ سابق. فيما يتعلق بالمقاصير الثلاث التي لا تزال قائمة، فإن عبادة الآلهة أسهلُ بكثيرٍ في فهمها من خلال مختلف البرامج الزخرفيَّة الموجودة في هذه المقاصير الثلاث مقارنةً بتحليل المستويات الأثريَّة؛ ذلك بسبب قلَّة العناصر الموجودة التي يمكن جمعُها كي تزيدَنا فهمًا للمساحات. غير أن اكتشاف الكثير من الودائع أوضح الفكرة التي لدينا عن الأماكن، وهي تشملُ في معظمها التماثيلَ البُرُنْزيَّة الصغيرةَ أو الأواني المودعة، والمرتبطة بأوزيريس، سواء أكانت مرتبطةً بأساساتِ المباني أم بالطقوس المُؤدَّاة فيما بعد.

وفي الواقع، فإن الإشغالات اللاحقة للمنطقةِ تقدمُ معلوماتٍ ثريَّةً حول استمراريَّة المواقع والعبادات. فالبنايات، في أغلبها، تم ترميمُها وإدراجُها في إطارٍ مكانيٍّ أكثر اتساعًا، على الرغم مما حدث من تعدُّد مراحل الهدم وإعادة الإشغال فيما بين القرنين الخامس والثالث ق. م. ويبدو أن عبادة أوزيريس قد استمرت في بعض هذه المراحل، كما يتضح من ترميم الآثار، ووجود التماثيل البُرُنْزيَّة الصغيرة، والقوالب وخاصةً بعض الودائع التي تشمل العملاتِ المعدنيَّةَ البطلميَّة، وكِسْراتِ تماثيلِ أوزيريس (الحيَّة المقدسة، وريش النعام)؛ وهو ما تم اكتشافُه خلال بعضِ أعمالِ تهيئة الموقع. أما المراحل اللاحقة، فيما بين القرنين الثاني والأول ق. م.، ثم القرون الثلاثة الأولى الميلاديَّة، فهي تُقدِّم كمًّا وافرًا من المعلومات؛ ولكنَّ التغييراتِ الكثيرةَ التي حدثت في هذا القطاع لم تترك سوى عددٍ قليلً جدًّا من البقايا التي تعكس العبادات السابقة.

لوران كولون (المعهد الفرنسي للآثار الشرقية/المدرسة التطبيقيَّة للدراسات العليا - علوم وآداب باريس)، سيريل ﭼﻴﻭرﭼﻰ (المعهدُ القوميّ للبحوث الأثريَّة الوقائيَّة)

Bibliographie

- L. Coulon, C. Giorgi, Rapport annuel sur la fouille des chapelles osiriennes nord de Karnak dans le rapport d’activité de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale (BIFAO-Suppl.) depuis 2000.

- L. Coulon, D. Laisney, « Les édifices des divines adoratrices Nitocris et Ânkhnesnéferibrê au nord-ouest des temples de Karnak (secteur de Naga Malgata) », Cahiers de Karnak 15, 2015, p. 81-171.

- L. Coulon, « Les chapelles osiriennes de Karnak. Aperçu des travaux récents », BSFE 195-196, juin-octobre 2016, p. 16-35.

- L. Coulon, A. Hallmann, F. Payraudeau, « The Osirian Chapels at Karnak: An Historical and Art Historical Overview Based on Recent Fieldwork and Studies », in E. Pischikova, J. Budka, K. Griffin (éd.), Thebes in the First Millennium BC. Art and Archaeology of the Kushite Period and Beyond, Proceedings of the International Conference held in Luxor, 25-29th September, 2016, GHP Egyptology 27, Londres, 2018, p. 271-293.

- F. Gombert-Meurice, F. Payraudeau (éd.), Servir les dieux d’Égypte. Divines adoratrices, chanteuses et prêtres d’Amon à Thèbes, catalogue d’exposition, musée de Grenoble, 24 octobre 2018-27 janvier 2019, Paris, 2018.

- Page web Karnak - sanctuaires osiriens archivée (2013)

Présentation des travaux de la Mission archéologique française des sanctuaires osiriens de Karnak par Laurent Coulon, directeur de la mission en 2024

تقديم لأعمال البعثة الآثارية الفرنسية للمقاصير الأوزيريَّة بالكرنك

English subtitles - مصحوبة بترجمة نصية للعربية

La chapelle d'Osiris Ounnefer (2024)

مقصورة أوزيريس أون نفر

Directeurs de la mission : Laurent Coulon (Collège de France, AOROC UMR 8546) & Cyril Giorgi (INRAP)مديري البعثة: لوران كولون (كولاچ دي فرانس) و سيريل چيورچي (المعهد الوطني للدراسات الأثرية الوقائية)