Deir el-Médina

| Noms anciens | st-aAt «La Grande Place», puis st-maAt (Hr jmnty WAst) «La Place de Vérité (à l’occident de Thèbes)» |

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.dbee-75cd |

IdRef IdRef | 027231771 |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 1917 |

Deir el-Médina, mission d’étudeOpération de terrain 17148

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Misr University for Science & Technology (MUST)

🔗 University of Copenhagen

🔗 University of Vienna

🔗 The Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Cofinancements

🔗 Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie

Dates des travaux

janvier - février

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2023 : 10.4000/baefe.8324

2021 : 10.4000/baefe.6243

2020 : 10.4000/baefe.2985

2019 : 10.4000/baefe.996

➣ Site(s) de la mission

https://www.facebook.com/DEMlouxor/

Participants en 2024

Les ostraca littéraires de Deir el-Medina. Étude et publicationAction spécifique 17431

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Égypte nilotique et méditerranéenne (UMR 5140, Equipe ENiM)

🔗 Projet Ramses

Cofinancements

🔗 Égypte nilotique et méditerranéenne (UMR 5140, Equipe ENiM)

Dates des travaux

janvier - décembre

Participants en 2024

Étude des ostraca hiératiques non littéraires de Deir el-MedinaAction spécifique 17432

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie

Cofinancements

Dates des travaux

janvier - février

Participants en 2024

| Pierre Grandet | égyptologue, enseignant | Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie, Paris / Musée du Louvre, Paris |

| Renaud Pietri | égyptologue, post-doctorant | Université de Liège |

Le site historique de Deir el-Médina

Le site a été choisi au début du Nouvel Empire, probablement sous le règne de Thoutmosis Ier, lorsqu’il a été décidé que les tombes royales seraient creusées non loin de là, dans la Vallée des Reines et la Vallée des Rois. L’emplacement des chantiers royaux était alors directement accessible par les artisans chargés des travaux. Le village a connu plusieurs phases d’agrandissement avant d’être abandonné à la fin de la XXe dynastie, durant le règne de Ramsès XI. Les habitants qui vivaient là étaient placés sous la tutelle du vizir et entièrement pris en charge par l’administration royale qui leur fournissait à la fois leur moyen de subsistance, comme les denrées alimentaires, les combustibles, les vêtements, ainsi que les outils et matériaux utilisés pour leur travail. Chaque foyer bénéficiait d’une maison et d’une concession funéraire dans le cimetière occupant le flanc de la colline à l’ouest du village. Le travail de chantier était très organisé, réparti entre deux équipes : l’équipe de gauche et celle de droite. Chacune était composée d’un chef des travaux assisté de surveillants, de scribes comptables, de tailleurs de pierre, de sculpteurs, de peintres, de maçons, de charpentiers. Des habitations plus rudimentaires aménagées sur une crête de la montagne et près des tombes royales permettaient aux équipes de ne pas avoir à retourner chaque jour jusqu’au village dans le vallon de Deir el-Médina.

La mission de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire (Ifao)

Après les premières fouilles italiennes puis allemandes au début du xxe s., l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire obtient la concession de Deir el-Médina en 1917. Entre 1921 et 1951, l’égyptologue Bernard Bruyère est chargé de dégager et d’étudier l’ensemble du site. La documentation archéologique et épigraphique qu’il met au jour est si abondante que son étude et sa publication sont encore poursuivies aujourd’hui sur le terrain par une équipe de chercheurs venus de plusieurs pays. Cette ouverture aux collaborations internationales, qui a été encouragée ces dernières années, trouve aussi un écho au niveau local. Des étudiants en égyptologie ou des restaurateurs égyptiens en formation sont associés à ces projets afin qu’ils acquièrent expérience et compétences techniques. La mission assure également des opérations d’entretien et les travaux d’accessibilité du site pour le public, ce qui nécessite de trouver un équilibre entre conservation, mise en valeur et poursuite des recherches archéologiques. Les approches adoptées sont variées. À côté des opérations importantes de restauration, d’autres actions garantissent la pérennité du site. Un travail de consolidation des maçonneries est réalisé chaque année dès qu’une brèche apparaît dans les monuments ouverts au public, ou qu’un effondrement provoque des risques structurels pour l’ensemble ou une partie des édifices. Des enduits sacrificiels sont régulièrement posés sur le sommet des murs du village afin que l’érosion naturelle dégrade cet enduit plutôt que la surface originale. Enfin, les vestiges les plus fragiles sont protégés par un système de couverture. Ces opérations vont de pair avec la mise en valeur du site. Une série de dispositifs significatifs a été installée afin de rendre les monuments plus compréhensibles auprès des visiteurs qui en arrivant sur le site passent par un espace d’accueil et d’information où des documents pédagogiques, plans et maquettes, leur indiquent les particularités de l’endroit où ils se trouvent. La mission prend également en charge les aménagements nécessaires pour permettre l’accès des monuments aux visiteurs, à la demande du ministère des Antiquités égyptiennes (MoA).

Les fouilles sont désormais arrêtées afin de rediriger les moyens vers la restauration des monuments du site et de recentrer le projet scientifique sur le travail de documentation. Les activités des dernières missions se sont concentrées sur la restauration et la publication des tombes inédites, la restauration des espaces de cultes du Nouvel Empire situés au nord du site et sur l’étude des objets découverts par B. Bruyère, actuellement conservés dans les magasins du MoA.

L’étude des monuments funéraires

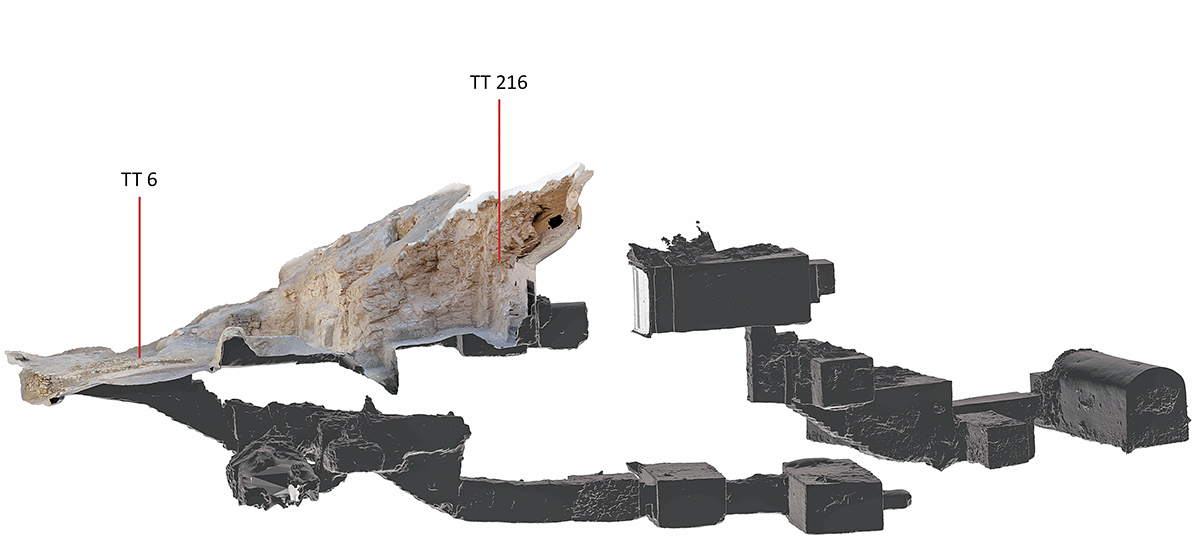

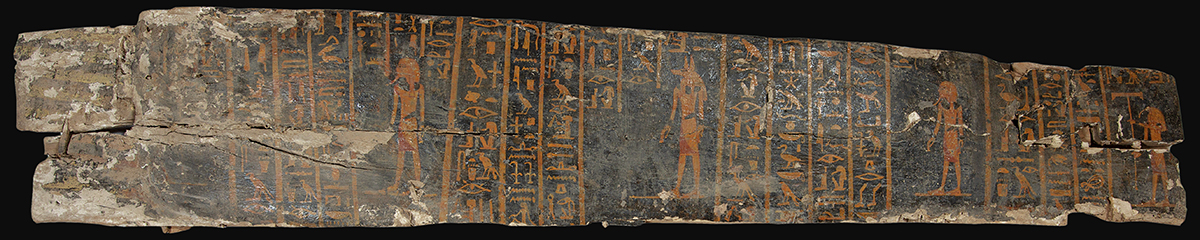

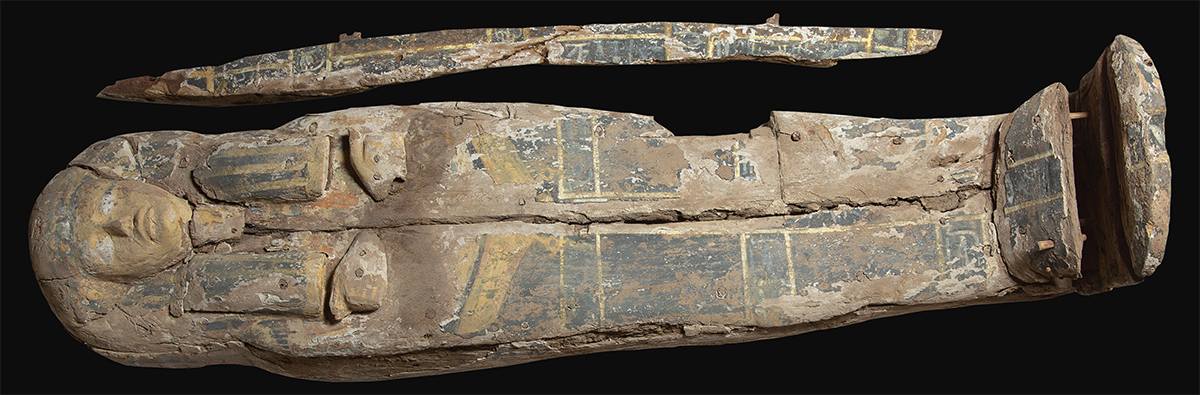

Le cimetière comprend une soixantaine de tombes décorées de scènes peintes ou gravées, pour la majorité d’époque ramesside. La méthodologie pour l’étude et la publication des tombes a beaucoup évolué ces dernières années. Elle privilégie une démarche holistique qui prend en compte, outre le monument lui-même, également le contexte et l’environnement dans lesquels il a été creusé. Topographe, photographe, céramologue, architecte, géologue, anthropologue, paléographe et restaurateur contribuent à une approche interdisciplinaire qui génère de nouvelles perspectives de recherche. Ainsi la photogrammétrie est utilisée pour chaque tombe étudiée. Le modèle 3D qu’elle permet de générer offre la possibilité de reconstituer des espaces en réalité virtuelle et de réaliser des vidéos immersives à 360°. Couplée à une analyse géoarchéologique, qui enrichit la reconstitution de données physiques réelles et inscrit le monument reconstitué dans son environnement géologique, cela produit des données nouvelles sur la manière dont les Égyptiens anciens ont interagi avec leur milieu, ainsi que sur les phases de creusement des monuments, sur les raisons de leur détérioration et sur les phénomènes naturels qui les menacent. Par exemple, cette technique a permis de comprendre l’architectonique de la tombe du responsable d’équipe Neferhotep (TT 216), inhumé dans le plus grand monument privé de Deir el-Médina. Le modèle 3D en a relevé la singularité. Les données récoltées portaient sur la position de la tombe, placée sur l’une des terrasses les plus hautes du site, qui a été choisie afin d’établir une connexion au moins visuelle avec le temple funéraire de Ramsès II, dont Neferhotep a réalisé la tombe ; ensuite sur sa structure, avec son accès par un escalier monumental à deux pans, afin de relier le monument à des voies processionnelles utilisées pour transporter les statues des divinités ; enfin, sur son plan, notamment des parties souterraines, qui montrent que le propriétaire a cherché, autant que possible et sans mettre en danger la structure du monument, à se rapprocher du caveau de la tombe voisine (TT 6) qui appartenait à son père Nebnefer.

La participation des restaurateurs au projet de publication d’une tombe est aussi un élément important du processus de la recherche. Leur intervention ne se limite pas au nettoyage : le diagnostic posé sur l’état des peintures nécessite un examen détaillé, sous différents types d’éclairage et très près de la paroi, qui offre souvent des observations précieuses sur les techniques des artisans, les repentirs, les ajustements, et qui contribue à reconstituer l’histoire du décor.

L’étude du matériel archéologique

En parallèle de la publication des tombes, la mission a repris l’étude des objets encore inédits conservés dans les magasins du site. Un nombre très important de petites figurines en céramique représentants des animaux, le dieu Bès ou des femmes nues sont en cours de documentation. Une équipe d’anthropologues a découvert la momie d’une femme recouverte de plus de trente tatouages figuratifs représentant des vaches sacrées, des serpents et des hiéroglyphes. Cette découverte exceptionnelle apporte des informations inédites sur la place éminente que pouvait avoir les femmes dans la sphère religieuse à Deir el-Médina. D’autres corpus d’objets sont en cours d’étude comme un lot d’appuis-tête, des stèles inscrites, des tables d’offrandes, un ensemble d’ostraca figurés, un lot d’outils utilisés par les peintres, autant d’objets qui permettront d’apporter de nouvelles informations sur la vie privée des habitants de Deir el-Médina, sur leur tradition, mais aussi sur l’organisation et la hiérarchie des équipes de travail dans la Vallée des Rois. La plupart de ces objets datent de l’époque ramesside, si bien que nous connaissons peu de choses des ouvriers chargés de fabriquer et décorer les tombes des pharaons de la XVIIIe dynastie. Mais des travaux récents ont permis d’établir que des signes inscrits sur divers types d’objets de cette période correspondaient à des marques personnelles qui identifiaient la propriété ou le destinataire du bien marqué. Plusieurs objets portant ces marques sont conservés dans les magasins du site. Leur étude permettra de reconstituer tout un pan de l’organisation administrative du site à la XVIIIe dynastie.

Cédric Larcher (Ifao)

The historic site of Deir el-Medina

The site was chosen at the beginning of the New Kingdom (probably during the reign of Tuthmosis I) when it was decided that royal tombs would be carved out of the rock not far from there, in the Valley of the Queens and in the Valley of the Kings. The location of these royal sites was then directly accessible for the artisans charged with the work. The village knew several phases of growth before being abandoned during the reign of Ramesses XI at the end of the 20th Dynasty. The inhabitants who lived there were placed under the supervision of the vizier and were entirely provided for by royal administration. This furnished them constantly with their means of subsistence such as food rations, firewood, clothes, as well as the tools and materials needed for their work. Each household was granted a house and a funerary concession in the cemetery which occupied the hillside to the west of the valley.

Work in the royal tombs was very organised, being divided into two gangs: one for the left side and one for the right. Each gang consisted of a Chief Workman who was assisted by supervisors, accounting scribes, painters, masons and carpenters. Very rudimentary dwellings were constructed near the royal tombs in a hollow in the mountains which allowed the gangs to live temporarily near their place of work, rather than return each day to the village in Deir el-Medina’s little valley.

The Mission of the French Institute for Oriental Archaeology (IFAO)

After the first excavations by Italians, then the Germans at the start of the 20th century, the IFAO obtained the concession of Deir el-Medina in 1917. Between 1921 and 1951, the Egyptologist Bernard Bruyère held responsibility for clearing and studying the whole site. The archaeological and epigraphic documentation that he undertook is so abundant that its study and publication are still underway today in the field, being conducted by a team of researchers coming from several countries. This openness to international collaboration, which has been encouraged in the recent years, also has local parallels. Egyptian students of Egyptology and restorers in training are associated with the projects so that they can acquire experience and technical skills. The mission also undertakes maintenance activities and work relating to site accessibility for the public, which necessitates finding a careful balance between conservation, site management and archaeological research.

A variety of activities are conducted. In addition to important tasks of restoration, other activities guarantee the endurance of the site. Each year masonry is consolidated as soon as a gap appears in monuments that are open to the public, or when a collapse induces structural risks for the whole or part of a structure. Surface coatings are regularly applied to the tops of the village walls so that natural degradation reduces this layer rather than the original surface. Finally, the most fragile remains are protected by a protective covering system. These activities go hand in hand with enhancing the site. A series of significant displays have been set up in order to make the monuments more comprehensible to the visitors who, when arriving at the site, pass by a welcome and information area. There, didactic documents, plans and models point out those features that are particular to the place they are visiting. In addition, at the request of the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA), the mission is in charge of the necessary improvements which enable visitors to access the monuments.

At the present time excavation has ceased so that resources can be redirected to the restoration of the site’s monuments and to refocus scholarly projects towards the task of documentation. The activities of the most recent missions have been concentrated on the restoration and publication of unpublished tombs, the restoration of New Kingdom cultic areas situated to the north of the site, and the study of the objects discovered by B. Bruyère which are currently stored in MoTA magazines.

The study of funerary monuments

The cemetery comprises about sixty tombs which were decorated with painted scenes or carved, the majority of which date to the Ramesside period. The methodology for studying and publishing tombs has evolved considerably over the last few years. It involves a holistic approach which, in addition to the monument itself, takes into account the context and the environment into which it is located. Topographers, photographers, ceramologists, architects, geologists, anthropologists, palaeographers and restorers combine to form an interdisciplinary approach which generates fresh research perspectives. Thus, photogrammetry is now employed in each tomb studied. The 3D model which it creates enables areas to be reconstructed in virtual reality and immersive 360° videos to be produced. Coupled with a geoarchaeological analysis, which facilitates the reconstruction of actual physical data and sets the reconstructed monument in its geological environment, the new data produced are revelatory. They inform about the manner in which the Egyptians interacted with their surroundings; about constructional phases when the monuments were being cut into the rock; about the reasons for their deterioration; and on the environmental elements which threaten them. A case in point is the tomb of the Chief Workman Neferhotep (TT 216), who was buried in the grandest private monument at Deir el-Medina, where this approach has enabled us to understand the complex architecture. The 3D model has revealed its highly unusual nature. Data gathered precisely record the position of the tomb on one of the highest terraces at the site, a location which had been chosen to establish a connection (a visual one at least) with the funerary temple of Ramesses II, the king whose tomb Neferhotep had participated in creating. Data recorded also throws light on the monument’s configuration, with its monumental two-sided stairway which links the monument with processional ways used to transport statues of divinities. Finally, data has been gathered on its design, especially its subterranean areas which indicates how the owner had sought, as much as was possible and without endangering the structure of the monument, to be adjacent to the underground areas of the neighbouring tomb (TT 6) which belonged to his father, Nebnefer.

The participation of restorers to the task of publishing a tomb is also an important consideration in the process of research. Their intervention is not just limited to cleaning. Investigation regarding the state of the paintings requires detailed examination under different types of lighting and being particularly close to the wall. Often this proximity enables significant observations to be made concerning artisans’ techniques, the alterations and adjustments made, which helps to reconstruct the decorations’ history.

The study of the archaeological material

Parallel with the publication of the tombs, the mission has resumed the study of unpublished objects stored in magazines at the site. A significant number of small figurines representing animals, the god Bes and naked women are in the process of being published. A team of anthropologists have discovered the mummy of a woman whose skin is covered with more than thirty figurative tattoos representing sacred cows, snakes and hieroglyphs. This exceptional discovery brings fresh information about the prominent place that women may have held at Deir el-Medina within the sphere of religion. Other corpora of objects which are being studied include a variety of headrests, inscribed stelae, offering tables, a collection of figured ostraca, and an assortment of tools used by the painters. In addition, objects are providing fresh information about the private life of Deir el-Medina’s inhabitants, their traditions, as well as about the organisation and hierarchy of the gangs who worked in the Valley of the Kings. Most objects date to the Ramesside period, while we know little about the workers responsible for the making and decorating of pharaohs’ tombs during the 18th Dynasty. However, recent study has enabled us to establish that signs which were written on various types of objects of this period correspond to personal marks which identify the owner or the recipient of the item marked. Several objects bearing these marks are stored in the magazines at site. Study of them will enable us to reconstruct a significant aspect concerning administrative organisation at the site during the 18th Dynasty.

Cédric Larcher (IFAO)

الموقعُ التاريخيُّ لدَيْرُ المَدِينَة

تم اختيارُ الموقع في بداية الدولة الحديثة، ربما خلال عهد تحتمس الأول، عندما تقرَّر أن يتم حفر المقابر المَلَكيَّة في مكانٍ قريبٍ من وادي الملكات والملوك؛ حيث كان يمكن للحرفيين المسئولين عن تلك الأعمال الوصول مباشرةً إلى مواقع الأعمال المَلَكيَّة. وقد شهدت القريةُ عدَّةَ مراحل من التَّوْسعَة قبل أن تُهجر في نهاية الأسرة العشرين، إبَّان عهد رمسيس الحادي عشر. وكان السكان الذين عاشوا في هذا الموقع تحت وصاية الوزير، تتكفل الإدارة المَلَكيَّة بهم بالكامل، وتزودهم في الوقت نفسه بوسائل المعيشة، مثل المواد الغذائيَّة والوقود والملابس؛ وكذلك الأدوات والمواد التي تُستخدم في عملهم. كان لكُلِّ أسرةٍ بيتٌ ومكانٌ مخصَّصٌ للدَّفْن في المقابر التي تشغل جانبَ التَّلِّ غرب القرية. تميَّز العملُ في الموقع بالنظام التام حيث كان مقسمًا بين فريقين: فريق اليسار وفريق اليمين. كل فريقٍ يتألَّف من رئيس الأعمال بمساعدة المشرفين، والكَتبَة المحاسبين، وقاطعي الحجارة، والنحَّاتين، والرسَّامين، والبنَّائين، والنجَّارين. هذه المساكن البسيطة للغاية والمبنية على قمَّة الجبل بالقرب من المقابر المَلَكيَّة للفِرَق سهَّلت للعاملين عدم العودة يوميًّا إلى القرية، في الوادي الضيِّق لدَيْرُ المَدِينَة.

بعثة المعهد الفرنسيّ للآثار الشرقيَّة

حصل المعهدُ الفرنسيُّ للآثار الشرقيَّة في القاهرة على حق امتياز موقع دَيْرُ المَدِينَة عام ١٩١٧، وذلك بعد الحفائِرِ الإيطاليَّة الأولى ثم الألمانيَّة في بداية القرن العشرين. وفيما بين الأعوام ١٩٢١ و١٩٥١، قام عالِمُ المصريَّات، برنار برويير بالكشف عن الموقع بأكمله ودراسته. ويُعدُّ التوثيقُ الأثريُّ والإبيجرافيُّ الذي قدمه وفيرًا؛ لدرجة أن دراساته وإصداراته لا تزالُ متواصلةً حتى اليوم في هذا المجال بمعرفةِ فريقٍ من الباحثين يأتون من الكثير من البلدان. هذا الانفتاحُ على التعاون الدوليّ الذي تم تشجيعه في السنوات الأخيرة له أيضًا صدَاهُ على المستوى المحليّ؛ حيث يشارك طلابُ علم المصريَّات أو المُرمِّمُون المصريون تحت التدريب في هذه المشروعات لاكتساب الخبرة والمهارات التِّقْنيَّة. توفرُ البعثة أيضًا عمليَّات الصيانة وإمكانيَّة الوصول إلى الموقع بالنسبة إلى الجمهور؛ مما يتطلب تحقيقَ التوازنِ بين حفظِ الموقعِ وإبرازهِ من ناحية، والبحث الأثريّ المستمر من ناحيةٍ أخرى مع تنوُّع المناهج المُتَّبعة. وإلى جانب عمليات الترميم الرئيسة، هناك إنشاءاتٌ أخرى تضمن استمراريَّة الموقع. يتم تنفيذ أعمال تقوية البناء كُلَّ عامٍ بمجرد ظهور صدع في الآثار المفتوحة للجمهور، أوعندما يتسبَّب انهيارٌ ما في مخاطر هيكليَّة لجميع الأبنية أو جزء منها. ويتم وضع الدهانات بشكل منتظم على قمَّة جدران أبنية القرية؛ بحيث يؤدى التآكل الطبيعيّ إلى إتلاف هذا الطلاء عوضًا عن السطح الأصليّ. وأخيرًا، تتمُّ حماية البقايا الأكثر هشاشةً بواسطة نظام تغطية. وتسير هذه العمليات جنبًا إلى جنب مع تطوير الموقع. وقد تمَّ إعداد مجموعة من الترتيبات اللازمة لتسهيل عملية فهم المعالم الأثريَّة بالنسبة للزائرين الذين - عندما يَصلُون إلى الموقع - يمرُّون من خلالِ منطقةِ استقبالِ وتزويد معلومات؛ حيث تتوافر وثائق إرشاديَّة وخرائط ومُجسَّمات للمكان المتواجدين فيه. تدعم البعثةُ أيضًا الترتيبات اللازمة للسماح للزائرين بالوصول إلى المعالم الأثريَّة، وذلك بناء على طلبٍ من وزارة الآثار المصريَّة.

غير أن أعمال التنقيب قد توقفت الآن من أجل إعادة توجيه الإمكانات المتاحة نحو ترميم الآثار في الموقع وإعادة تركيز المشروع العلميّ على أعمال التوثيق. ركَّزت أنشطةُ البعثاتِ الأخيرة على ترميم ونشر المقابر غير المعروفة، وترميم أماكن العبادات من عصر الدولة الحديثة، الواقعة شمال الموقع، وعلى دراسة القِطَع التي اكتشفها ب. برويير، والمحفوظة حاليًّا في مخازن وزارة الآثار.

دراسة الآثار الجنائزيَّة

تضم الجبانة قُرَابَة ستين مقبرةً مُزيَّنةً بمشاهد مرسومة أو محفورة، ترجعُ في معظمها لفترة الرَّعامِسَة. تطورت منهجيَّة دراسة ونشر المقابر بشكلٍ كبيرٍ في السنوات الأخيرة، فهي تركِّز على اتِّباع منهج كُلِّيٍّ يأخذ في الاعتبار، بالإضافة إلى الأثر نفسه، السياق والبيئة اللتين حُفر فيهما الأثر. كُلٌّ من الطُّبُوغرافي، والمصور، والمتخصص في دراسة الخَزَفْ، والمعماريّ، واﻟﭼﯿوﻟوچيّ، والأنثروبولوچيّ، والمتخصص في الكتابات القديمة، والمُرمِّم؛ الجميع يساهمون في اتِّباعِ نَهْجٍ مُتعدِّد التخصُّصات يستطيع أن يولِّد آفاقًا بحثيَّةً جديدة. هكذا يتم استخدام المسح التصويريّ لكل مقبرة تمَّت دراستها، ويوفر النموذجُ ثلاثىُّ الأبعاد الناتج عن هذا المسح إمكانيةَ إعادة بناء المساحات في الواقع الافتراضي، وإعداد مقاطع ﭬيديو جيدة للغاية بزاوية ٣٦٠ᵒ. وإلى جانب التحليل الأثريّ-الجغرافيّ، الذي يُثرى إعادة بناء البيانات الماديَّة الحقيقيَّة ويُدرج الأثر الذي أُعيد بناؤه في بيئته اﻟﭼﯿوﻟوﭼﯿَّﺔ، فإن تلك التِّقْنية تُنتج بياناتٍ جديدةً عن الطريقة التي تعامل بها المصريون القدماء مع بيئتهم؛ وكذلك مراحل حفر الآثار وأسباب تدهورها والظواهر الطبيعيَّة التي تهددها. على سبيل المثال، ساعدت هذه التِّقْنية على فهم الفلسفة المعماريَّة لمقبرة قائد الفريق نفرحتب (المقبرة ٢١٦)، الذي دُفن في الأثر الخاص الأكبر في دَيْرُ المَدِينَة، وقد كشف النموذجُ ثلاثيُّ الأبعاد عن هذا التفرُّد. وركَّزت البياناتُ التي تم جمعها على موقع المقبرة، المقامة على واحدة من أعلى المدرجات في الموقع، والتي تم اختيارها لإقامة اتصال مرئيّ على الأقل مع المعبد الجنائزيّ لرمسيس الثاني، والذي قام نفرحتب بتنفيذ مقبرته؛ كما ركَّزت البيانات على هيكل المقبرة، ومدخلها المزوَّد بدَرَجٍ ضخم، لربط الأثر بالمسارات التي تمرُّ من خلالها المواكب لنقل تماثيل الآلهة؛ وأخيرًا ركزت البيانات على تصميم المقبرة، ولا سيَّما في الجزء الواقع أسفل الأرض، والتي تبين أن صاحب المقبرة سعى، قدر الإمكان، ودون تعريض بنية الأثر للخطر، إلى الاقتراب من قبو المقبرة المجاورة (المقبرة ٦) التي تخصُّ أباه نب نفر.

إن مشاركة المُرمِّمين في مشروع نشر مقبرة، هو عنصر مهم في عملية البحث، حيث لا يقتصر تدخلهم على التنظيف فقط: هذا الأمر يتطلب تشخيص حالة الألوان فحصًا مُفصَّلًا، تحت أنواع مختلفة من الإضاءة وقريبة جدًّا من الجدار. هذه المشاركة تسفر غالبًا عن ملاحظات قيِّمة حول تقنيَّات الحِرَفيِّين، ما تمَّ التراجع عنه، والتعديلات تُسهم في إعادة صياغة تاريخ الزخرفة.

دراسة المواد الأثريَّة

استأنفت البَعْثةُ دراسة القطَع غير المنشورة والمحفوظة في مخازن الموقع، بالتوازي مع نشر المقابر. ويتم توثيق عدد كبير جدًّا من التماثيل الصغيرة من الخَزَفْ التي يمثل البعضُ منها أشكالَ حيواناتٍ أو الإله بِس أو سيِّدات عاريات. اكتشف فريق من علماء الأنثروبولوﭼيا مومياء امرأة مُغطَّاة بأكثر من ثلاثين من الوشوم التصويريَّة التي تمثل أبقارًا مقدسة وثعابين وحروفًا هيروغليفيَّة. ويوفر هذا الاكتشافُ الاستثنائيُّ معلوماتٍ غيرَ مسبوقةٍ عن المكانة البارزة التي يمكن أن تتمتع بها النساء في المجال الدينيّ في دَيْرُ المَدِينَة. كما تتم حاليًّا دراسة مجموعة أخرى من القِطَع مثل الكثير من مساند الرأس، واللوحات المنقوشة، وموائد القرابين، ومجموعة من الشقفات المُصوَّرة، والكثير من أدوات الرسَّامين، حيث ستوفر معلومات جديدة عن الحياة الخاصة لسكان دَيْرُ المَدِينَة، عن تقاليدهم؛ وكذلك عن تنظيم وتدرُّج الرُّتَب لفرَق العمل في وادي الملوك. ويعود تاريخ معظم هذه القطع إلى فترة الرعامسة؛ لهذا السبب فإننا نعرف القليل عن العمَّال المسئولين عن صنع وزخرفة مقابر الفراعنة في الأسرة الثامنة عشرة؛ غير أن الأعمال الأخيرة قد سمحت بإظهار أن العلامات المُسجَّلة على أنواعٍ مختلفةٍ من القطع في هذه الفترة، كانت متوافقةً مع العلامات الشخصيَّة التي حددت المِلكيَّة أو صاحب المتاع المشار إليه. ويتم حفظ الكثير من القطع التي تحملُ العلاماتِ في مخازنِ الموقع. وسوف تُسْهم دراسة هذه المواد في اقتفاء أثر جانبٍ هام من شكل التنظيمَ الإداريَّ للموقع في عصر الأسرة الثامنة عشرة.

سيدريك لارشيه (المعهد الفرنسيّ للآثار الشرقية)

Bibliographie

- N. Cherpion, J.-P. Corteggiani, La tombe d’Inherkhâouy (TT 359) à Deir el-Médina, MIFAO 128, Le Caire, 2010.

- H. Gaber, L. Bazin Rizzo, F. Servajean (éd.), À l’œuvre on connaît l’artisan … de pharaon ! Un siècle de recherches françaises à Deir el-Médina (1917-2017), catalogue d’exposition, Musée égyptien du Caire, 21 décembre 2017-5 février 2018, CENIM 18, Milan, 2017.

- P. Grandet, Catalogue des ostraca hiératiques non littéraires de Deîr el-Médînéh, DFIFAO 50, Le Caire, 2017.

- P. Marini, « Shabti-boxes and their representation on wall paintings in tombs at Deir el-Medina », in A. Dorns, S. Polis (éd.), Outside the Box. Selected papers from the conference “Deir el-Medina and the Theban Necropolis in Contact”, Liège, 27-29 octobre 2014, AegLeod 11, Liège, 2018, p. 281-300.

- G. Eschenbrenner-Diemer, A. Giulia de Marco, P. Marini, « Woodcraft in Deir el-Medina: from the manufactured object to the workshop », in Deir el-Medina through the Kaleidoscope, Museo Egizio di Turin, 8th-10th October 2018, sous presse.

- C. Larcher, D. Lefèvre, « The Monument of Neferhotep (TT 216) at Deir el-Medina », in Deir el-Medina through the Kaleidoscope, Museo Egizio di Torino, 8th-10th October 2018, sous presse.

- Une partie des archives de fouille de Bernard Bruyère, ainsi que des photographies des tombes de Deir el-Médina, est accessible en ligne sur le site de l’Ifao : https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bases/archives/bruyere/ ; https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bases/archives/ttdem/.

- Page web Deir el-Medina archivée (2019)