Forts et ports de l’Égypte médiévale

lieux stratégiques de l’Égypte médiévale, des Abbassides à Mohamed Ali (850-1840)

Responsable: Stéphane Pradines (archéologue, IFAO); Eric Vallet (historien, univ. Paris 1, CNRS - UMR 8167); Osama Talaat (historien, univ. du Caire et d’Aden)

Collaborations: Archéologues: Alison Gascoigne (univ. de Southampton); Kathrin Machinek (CEAlex); Sami Abdel el-Malik (SCA); Ahmad Šawqī (univ. ‘Ayn Šams) ; Yoko Shindo (univ. de Tokyo); Historiens: Frédéric Bauden (univ. de Pise); Elise Franssen (doctorante, univ. de Liège); Hussam Ismail (univ. ‘Ayn Šams); Tarek El-Morsi (chercheur associé, IREMAM et CEAlex); Abbès Zouache (chercheur associé, CNRS-UMR 5648 CIHAM); Historiens de l'Art: Rihāb Saïdi (univ. du Caire); Heba Yusuf (univ. de Helwan); Épigraphiste: Francesca Dotti (doctorante, EPHE); Topographe: Olivier Onézime (IFAO, INRAP).

Institutions partenaires:

- SCA;

- Université dʼʻAyn Shams;

- Université du Caire;

- Université de Helwan ;

- CEAlex;

- CNRS-UMR 8167 Orient et Méditerranée.

Programme partenaire: ANR MEDIAN.

Les recherches menées sur les fortifications médiévales égyptiennes sont à l'origine d'une base de données FortifOrient et d'un système d’informations géographiques. Les données recueillies, lors du précédent programme de l’Ifao, permettent maintenant de développer une étude spécifique de ces lieux de mémoire que sont les fortifications. Cet inventaire a permis de constater que les fortifications égyptiennes étaient presque toujours liées à des installations portuaires. Les autres forts sont localisés sur des axes commerciaux terrestres, le plus souvent en plein désert et liés à un point d’eau. Là aussi, le fort peut être considéré comme un havre de paix au centre du Sahara, dont les marges (sāḥil) sont désignées par le même terme que les rivages de la mer. Comprendre l’articulation entre fonctions portuaires et structures défensives nécessite un examen approfondi des sources écrites et des vestiges, afin de distinguer ce qui relève de la simple volonté de défense du territoire face aux menaces venues de la mer, du désir de contrôler les flux de marchandises et de voyageurs, ou d’isoler le port de son arrière-pays. L’organisation des sites portuaires fortifiés de la côte méditerranéenne est-elle identique à ceux de la mer Rouge ? Peut-on observer des stratégies différentes de défense des ports en fonction du rapport changeant de l’État égyptien à la puissance navale ?

Ce programme, en collaboration avec l’UMR 8167 - Orient et Méditerranée, permet d’enrichir la base de données du projet APIM : Atlas des Ports et Itinéraires maritimes de l’Islam médiéval. Du point de vue de l’histoire des ports, notre collaboration avec l’ANR MEDIAN, Les sociétés méditerranéennes et l’océan Indien, amène à replacer les ports fortifiés égyptiens dans un cadre méditerranéen et indo-océanique.

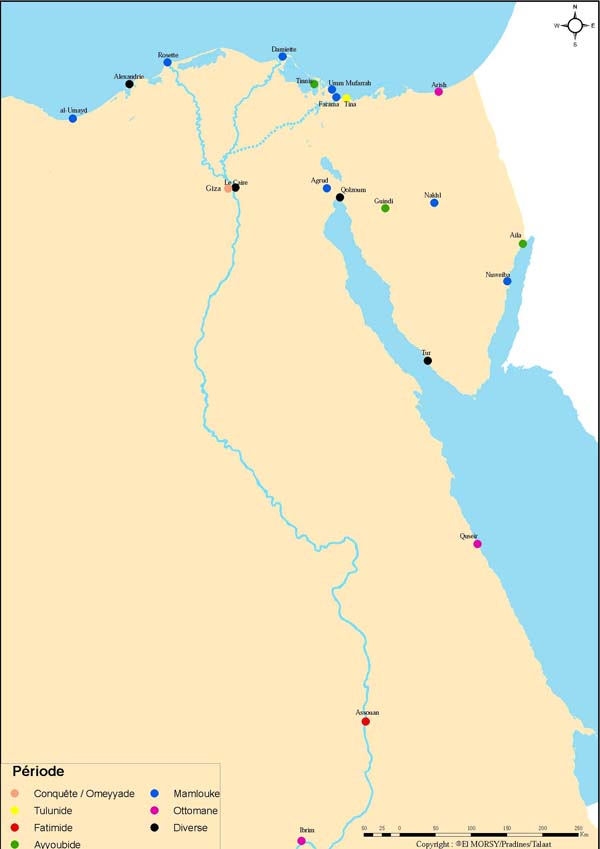

Concernant la localisation des fortifications égyptiennes, deux espaces concentrent la quasi-totalité des édifices militaires construits aux périodes médiévales et modernes : le delta du Nil et le Sinaï.

Le Delta égyptien est le premier de ces espaces géostratégiques, à la fois ouvert sur la mer Méditerranée et la vallée du Nil. Les fortifications toulounides, fatimides, ayyoubides et mamloukes protègent le littoral face aux agressions extérieures et contrôlent l'accès au fleuve, axe de pénétration dans le territoire. Le Caire forme le dernier verrou de ce delta tant convoité. Durant deux siècles de guerres, l'Égypte a joué un rôle important dans l'histoire des Croisades, mais les fortifications du Delta, depuis l'expédition de Baudouin 1er en 1118 jusqu’à la malheureuse tentative de saint Louis en 1249 et l’avènement des Mamlouks, n’ont pas retenu suffisamment l’attention des chercheurs. L’objectif de ce programme est de retracer cette histoire du Delta à travers une approche pluridisciplinaire. Pour la période médiévale, des sites archéologiques sont en cours de fouille et seront publiés prochainement, comme à Alexandrie (CEAlex) et Tinnis (Southampton Univ.). D’autres fortifications côtières du Delta feront l’objet de prospections et d’études monographiques, comme celles de Rosette, Mansourah, Damiette, Tina et Farama. Le travail d’inventaire réalisé pour la base de données a aussi permis de redécouvrir d’autres édifices militaires plus tardifs, datant de l’époque de Mohamed Ali, entre 1820 et 1848. Ces fortifications bastionnées, bâties dans le Delta, sont l’œuvre d’ingénieurs militaires français. L’axe central de ce réseau se situait au Caire où un arsenal alimentait en armes et en munitions ces postes avancés dans le Delta qui demeure, de Saint-Louis à Napoléon, l'entrée et le point faible de l'Égypte. Comme d'autres travaux effectués sous Mohamed Ali, ces forteresses marquent l'entrée de l'Égypte dans la modernité.

Le second espace stratégique est mieux connu, il s’agit du Sinaï et de l’isthme de Suez, terres de contact entre deux mondes, l'Afrique et l'Orient. Du Moyen Âge aux guerres israélo-arabes, cet espace « tampon » a été une zone de conflits. Un important travail historique et archéologique sur le Sinaï médiéval a déjà été réalisé par Jean-Michel Mouton. La base FortifOrient et le système d’informations géographiques sont venus augmenter ces données. Des travaux sur l’île de Graye, dans le golfe d'Aqaba, peuvent compléter les fouilles précédemment menées par l’Ifao sur la forteresse de al-Gundi (forteresse de Sadr). La forteresse ayyoubide, le port et le village de Graye sont entièrement à relever topographiquement et architecturalement. Ce site, qui a joué un grand rôle à l’époque des Croisades, est un lieu hautement stratégique. Enfin, une prospection topographique sur le site d’Agrud, à côté de Bir Suez, permettra de documenter ces forts caravaniers qui furent utilisés jusque sous Napoléon.

Actions prévues

- Travaux sur le terrain, prospections et relevés de fortifications égyptiennes, Tina, Farama, Tinnis, Agrud et Graye

- Exposition Saint Louis et l'Égypte, organisée avec la mairie d’Aigues-Mortes

- Organisation d'un colloque international : Ports et fortifications en islam médiéval (Méditerranée, mer Rouge, océan Indien)

- St. Pradines et O.Talaat, Guide des fortifications islamiques égyptiennes, Sca-Ifao.

- A. Gascoigne, dir., The Island City of Tinnīs: an archaeological study, Ifao.

- St. Pradines, O. Talaat, E. Vallet, Ports et fortifications en islam médiéval (Méditerranée, mer Rouge, océan Indien), Édition des Actes du colloque programmé, Ifao.

Forts and ports of medieval Egypt

strategic locations in medieval Egypt, from the Abbasids to Mohamed Ali (850-1840)

Supervisor: Stéphane Pradines (archaeologist, IFAO); Eric Vallet (historian, univ. Paris 1, CNRS - UMR 8167); Osama Talaat (historian, univ. of Cairo and of Aden)

Collaborators: Archaeologists: Alison Gascoigne (univ. of Southampton); Kathrin Machinek (CEAlex); Sami Abdel el-Malik (SCA); Ahmad Šawqī (univ. of Ain Shams); Yoko Shindo (univ. of Tokyo); Historians: Frédéric Bauden (univ. dof Pisa); Elise Franssen (PhD studen, univ. of Liège); Hussam Ismail (univ. of Ain Shams); Tarek El-Morsi (associate researcher, IREMAM and CEAlex); Abbès Zouache (associate researcher, CNRS-UMR 5648 CIHAM); Art Historians: Rihāb Saïdi (univ. of Cairo); Heba Yusuf (univ. of Helwan); Epigraphist: Francesca Dotti (PhD student, EPHE); Topographer: Olivier Onézime (IFAO, INRAP).

Partner institutions:

- SCA;

- University of Ain Shams;

- University of Cairo;

- University of Helwan;

- CEAlex;

- CNRS-UMR 8167 Orient et Méditerranée.

Programme partner: ANR MEDIAN.

Research into medieval Egyptian fortifications has led to the creation of a database entitled FortifOrient and to a geographic information system. The data gathered during the earlier IFAO project now allows for a more developed and specific study of these historical sites. The inventory that was drawn up has shown that Egyptian fortifications were almost always connected to port facilities. Any other forts are situated on terrestrial trade routes, most often in the middle of the desert and linked to a water point. There again, the fort can be viewed as a haven of peace in the centre of the Sahara, the edges of which (the sāḥil) are identified using the same term as for the seashore. An in-depth examination of written sources and physical vestiges is required in order to understand the linkage between port facilities and defensive structures. One must distinguish that which arises from the simple desire to defend territory from seaborne threats from the wish to control the movement of goods and people, or to isolate the port from its hinterland. Was the organisation of fortified ports on the Mediterranean coast the same as those of the Red Sea? Can one observe different defensive strategies for ports as a function of the changing relations of the Egyptian state to naval power?

This programme, in collaboration with UMR 8167 - Orient et Méditerranée, will contribute to the database of the project APIM (Atlas of ports and maritime itineraries of medieval Islam. From the standpoint of the history of ports, our collaboration with the ANR MEDIAN (Mediterranean Societies and the Indian Ocean) aims to situate the fortified Egyptian ports within a framework that is both of the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean.

As regards the location of Egyptian fortifications, almost all the military structures built during the medieval and modern periods are to be found in either in the Nile Delta or the Sinai.

The Egyptian Delta is the first of these geo-strategic areas, open to both the Mediterranean and the Nile Valley. Tulunid, Fatimid, Ayyubid and Mamluke fortifications protected the littoral from exterior threats and controlled access to the river that was the main route into the country. Cairo served as the final bolt securing the much-coveted Delta. Throughout two centuries of war, Egypt played an important role in the history of the crusades, but the fortifications of the Delta, from the invasion of Baldwin I in 1118 to the unsuccessful attempt of St Louis in 1249 and the coming of the Mamlukes, have never fully grabbed the attention of scholars. The intention of this programme is to retrace this history of the Delta through a multi-disciplinary approach. For the medieval period, certain archaeological sites are under excavation and will be published shortly, e.g. Alexandria (CEAlex) et Tinnis (Southampton Univ.). Other coastal fortifications of the Delta, such as Rosetta, Mansoura, Damietta, Tina and Farama, will be the object of investigations and monographs. The inventory developed for the database also led to the rediscovery of other, later military structures dating to the Mohamed Ali period, between 1820 and 1848. These bastioned forts built in the Delta were the works of French military engineers. The central pivot of this network was located in Cairo where an arsenal furnished the forward posts in the Delta with arms and munitions. From St Louis to Napoleon, the Delta was the entrance to and weak spot of Egypt and, as with other projects undertaken by Mohamed Ali, these fortresses mark the gateways to Egypt in the modern era.

The second strategic area is less well known. This is the Sinai and the Isthmus of Suez, the meeting point of two worlds: Africa and the East. From the middle ages until the Arab-Israeli wars, this "buffer" space has, in fact, been a conflict zone. Jean-Michel Mouton has already undertaken important historical and archaeological work on medieval Sinai and the FortifOrient database and GIS has added to this. Investigations on the Ile de Graye (Pharaoh's Island) in the Gulf of Aqaba will complement the excavations already undertaken by the IFAO at Al- Gundi citadel (Sadr citadel). The Ayyubid fort, the port and village of Graye still need a full topographic and architectural survey. This site, which played an important role at the time of the Crusaders, is a highly strategic point. Lastly, a topographic survey of the site of Agrud, next to Bir Suez, will provide documentation on the caravan forts that were used up until Napoleon's day.

Actions prévues

- Travaux sur le terrain, prospections et relevés de fortifications égyptiennes, Tina, Farama, Tinnis, Agrud et Graye

- Exposition Saint Louis et l'Égypte, organisée avec la mairie d’Aigues-Mortes

- Organisation d'un colloque international : Ports et fortifications en islam médiéval (Méditerranée, mer Rouge, océan Indien)

- St. Pradines et O.Talaat, Guide des fortifications islamiques égyptiennes, Sca-Ifao.

- A. Gascoigne, dir., The Island City of Tinnīs: an archaeological study, Ifao.

- St. Pradines, O. Talaat, E. Vallet, Ports et fortifications en islam médiéval (Méditerranée, mer Rouge, océan Indien), Édition des Actes du colloque programmé, Ifao.