Tanis

| Variantes | Tell Sân el-Hagar تل صان الحجر |

doi doi | 10.34816/ifao.2299-54fb |

IdRef IdRef | 027785866 |

| Missions Ifao depuis | 2017 |

Tanis : archéologie urbaine, géo-archéologie, histoireOpération de terrain 17114

Responsable(s)

Partenaires

🔗 Bureau d’études et de recherches archéologiques Eveha International (Éveha International)

🔗 Institut d’archéologie et d’ethnologie de l’Académie polonaise des sciences (IAE PAN)

Cofinancements

🔗 Bureau d’études et de recherches archéologiques Eveha International (Éveha International)

🔗 Nouvelle société des amis de Tanis

🔗 Fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie

Dates des travaux

septembre - novembre

Rapports de fouilles dans le BAEFE

2019 : 10.4000/baefe.1137

➣ Site(s) de la mission

https://www.ephe.psl.eu/recherche/unites-de-recherche/mission-francaise-des-fouilles-de-tanis-mfft

https://www.facebook.com/Mission-française-des-fouilles-de-Tanis-136306616998235

Participants en 2024

Situé à environ 120 km à vol d’oiseau au nord-est du Caire, le site archéologique de Tell Sân el-Hagar/Tanis est l’un des mieux conservés du delta du Nil. L’établissement fut fondé au tournant du Nouvel Empire et de la Troisième Période intermédiaire (XIe s. av. J.-C.). L’Égypte entrait alors, pour un temps, dans une période de division. Au sud, la puissance des grands prêtres d’Amon leur conférait le contrôle de tout le sud du pays depuis Thèbes. Au nord, le pouvoir des nouveaux souverains à partir de la XXIe dynastie ne s’étendait pas au-delà de la Basse Égypte. Les modifications du régime fluvial du bras le plus oriental du Nil, la branche pélusiaque, avaient entraîné l’abandon de l’ancienne résidence et base navale des Ramsès, Pi-Ramsès (aujourd’hui Qantir), bâtie dans le prolongement de l’antique capitale des rois Hyksôs, Avaris. Les nouveaux dynastes choisirent alors d’établir leur foyer à une vingtaine de kilomètres plus au nord. Au bord de la branche voisine du fleuve, dite tanitique, et de lagunes côtières, une large butte sableuse, vierge ou presque de toute construction, hors d’eau au moment de l’inondation annuelle, constituait un terrain idéal pour créer de toutes pièces un vaste établissement urbain et un nouveau port d’importance en Méditerranée orientale. Les rois des XXIe, XXIIe et XXIIIe dynasties, Psousennès Ier en tête, y firent bâtir des temples, ceux des XXIe et XXIIe dynasties également leur dernière demeure. Après l’avènement de la dynastie saïte dans l’ouest du Delta (VIIe s. av. J.-C.), Tanis resta une importante métropole religieuse, de taille toutefois plus modeste qu’auparavant, mais aux temples reconstruits et embellis à plusieurs reprises jusqu’à l’époque ptolémaïque (IVe-Ier s. av. J.-C.). La localité survécut jusqu’à la fin de l’époque byzantine avant d’être abandonnée.

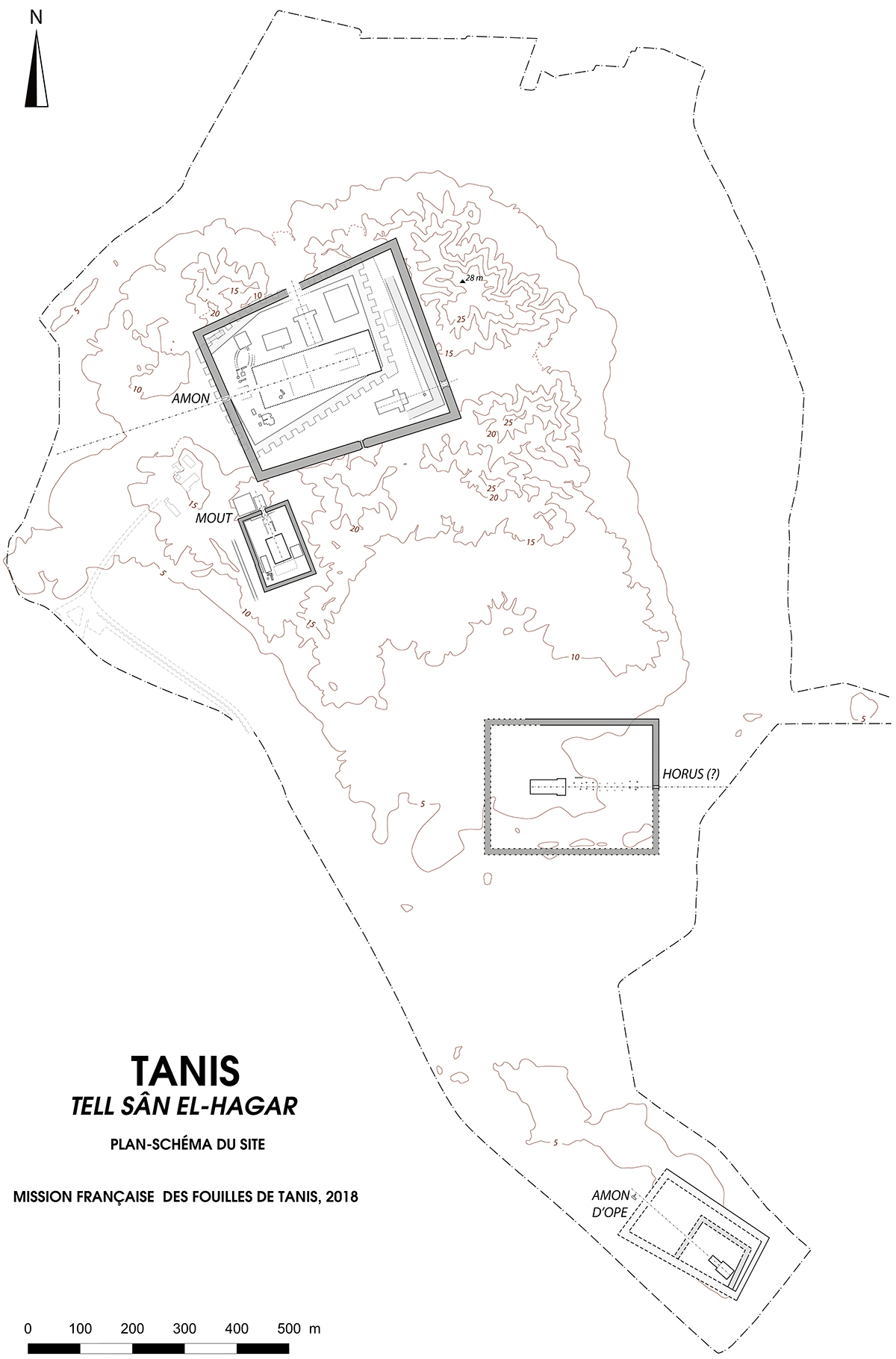

La cité paraît avoir été pensée comme une sorte de doublon de Thèbes de Haute Égypte, ce qui lui valut parfois le surnom de « Thèbes du Nord » : consacrés aux divinités de la triade thébaine, Amon, Mout et Khonsou, ses temples furent bâtis, comme à Karnak, au sein de deux grandes aires sacrées situées dans la partie nord de la ville, tandis qu’un sanctuaire d’Amon d’Opé, miroir du temple de Louqsor, en occupa l’extrémité sud. Plus tardivement, Tanis vit également se développer le culte d’Horus, principale divinité du delta oriental. Les enclos religieux étaient entourés d’une agglomération très étendue (plus de 200 ha), dont les hautes collines actuelles forment les vestiges majeurs érodés par de millénaires intempéries.

Bâtis en pierre, les sanctuaires furent sévèrement détruits à partir de l’Antiquité tardive. Ce qu’il en reste aujourd’hui tient davantage des ruines d’une carrière. Le calcaire qui formait l’essentiel de leurs maçonneries disparut presque entièrement dans les fours à chaux. Les éléments de pierre dure (granit, quartzite) – obélisques, statues, colosses, colonnes, stèles, blocs, etc. – sont les vestiges les plus spectaculaires aujourd’hui, pouvant donner au visiteur non averti la fausse impression que les édifices avaient autrefois été intégralement construits avec ces matériaux. Leur amoncellement plus ou moins chaotique donna au site, ainsi qu’à la localité moderne qui le jouxte, son nom moderne : Sân el-Hagar, « Tanis-les-Pierres ». Sur ces monuments, la présence massive d’inscriptions antérieures à la fondation de la ville, pour l’essentiel de l’époque ramesside (XIXe-XXe dynasties), déroutèrent un temps les premiers égyptologues, qui crurent que Pi-Ramsès et Avaris devaient également se trouver là. Les vestiges de ces dernières furent finalement découverts ailleurs. À leur abandon, leurs somptueux édifices de pierre avaient eux-mêmes constitué une source de matériaux avantageusement proche pour édifier les sanctuaires de la nouvelle capitale.

Identifiée dès le premier quart du XVIIIe s. comme les ruines de la Tanis de la Bible, Sân el-Hagar fut visitée en 1798 par les savants de l’Expédition Bonaparte, qui la décrivirent pour la première fois en détail. Dans la première moitié du XIXe s., quelques fouilles opérées par des aventuriers à la solde de diplomates épris d’antiquités donnèrent quelques belles statues. Des savants vinrent ensuite sur le site copier des inscriptions, mais c’est à Auguste Mariette, fondateur du service des Antiquités de l’Égypte, que l’on doit le premier dégagement majeur du temple d’Amon (1860-1864). Il y mit au jour quantités de statues et de reliefs, qui furent transportés au Musée égyptien du Caire au début du XXe s.

L’archéologue britannique William M. Flinders Petrie y fit également ses premières armes en 1884. Mais c’est à partir de 1929 qu’une mission française, dirigée par le professeur Pierre Montet, put se consacrer dans la durée à l’exploration systématique des aires sacrées d’Amon et de Mout. S’il en dégagea les traits majeurs, l’histoire retiendra surtout son extraordinaire découverte, à partir de 1939, au moment où l’Europe s’apprêtait à sombrer dans un conflit dévastateur, des tombeaux royaux et princiers des XXIe et XXIIe dynasties. Les vestiges de plus d’une quinzaine de sépultures, réparties en plusieurs ensembles, furent ainsi mis au jour. Quelques-unes d’entre elles, intactes, livrèrent de riches trésors (sarcophages de pierre et d’argent, masques d’or, parures et vaisselle précieuse, etc.) conservés au Musée égyptien du Caire, où ils sont sur le point de faire l’objet d’une nouvelle présentation.

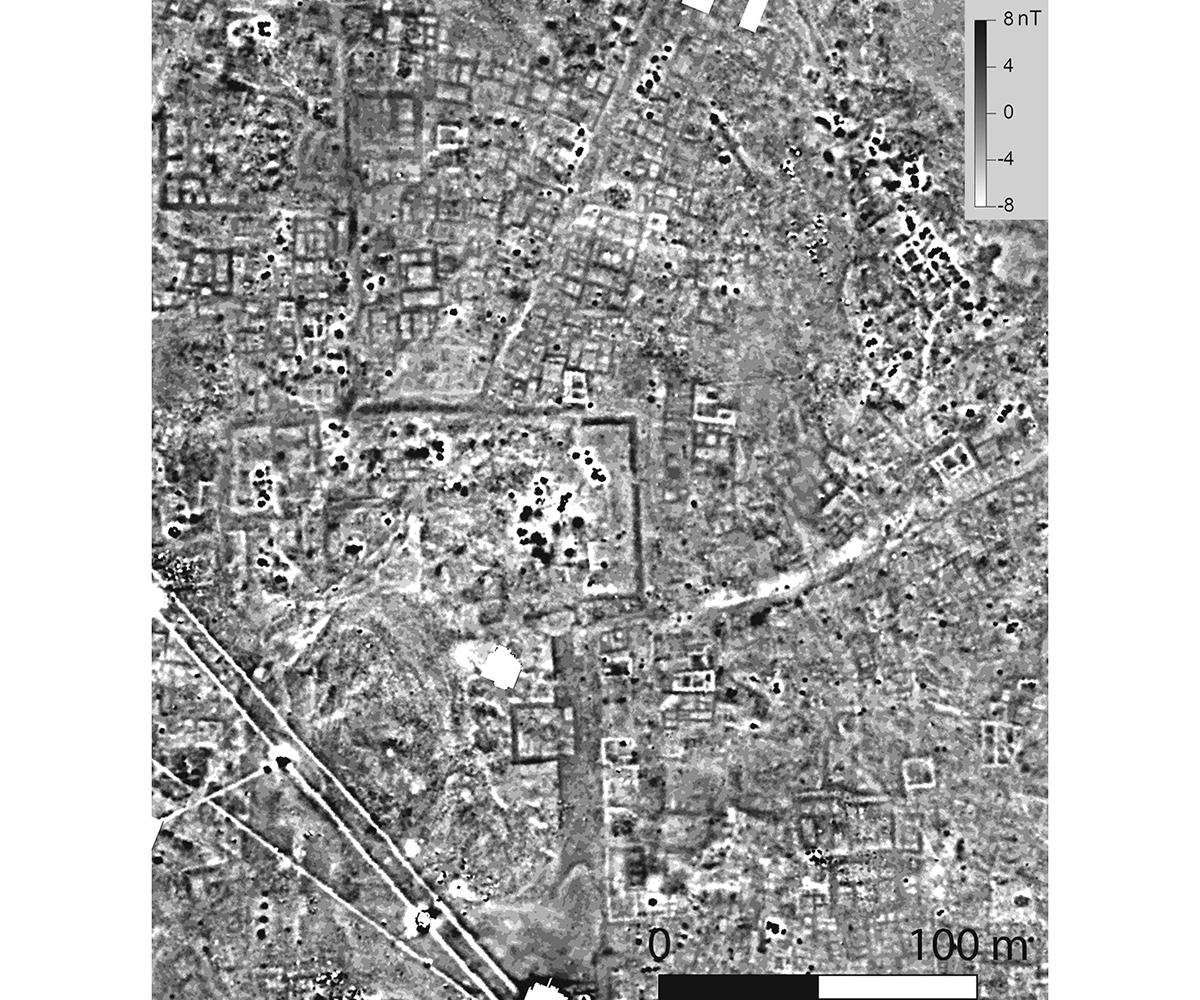

Interrompus en 1956, les travaux de la Mission Montet se poursuivent depuis 1965 sous l’égide de la Mission française des fouilles de Tanis (MFFT), qui consacre ses activités au réexamen méthodique des zones autrefois explorées, à la fouille de nouveaux secteurs, à l’étude globale du tell par le biais de prospections à grande échelle, et à la valorisation scientifique et patrimoniale des vestiges découverts (épigraphie, architecture, topographie, protection, conservation, mise en valeur). Créée avec l’appui de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, elle bénéficie du soutien de l’École pratique des hautes études (Paris-Sciences-Lettres), son institution de rattachement, et du ministère français de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, mais aussi du fonds Khéops pour l’archéologie et de la Nouvelle société des amis de Tanis. Les travaux sont menés en collaboration avec le ministère égyptien des Antiquités et en partenariat avec plusieurs organismes scientifiques français et européens (Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Sorbonne Université, département égyptien du musée du Louvre, CNRS, Académie polonaise des sciences, Eveha international, etc.).

François Leclère (EPHE-PSL, UMR 8546)

Situated about 120 km as the crow flies from north-east Cairo, the archaeological site of Tell San el-Hagar/Tanis is one of the best-preserved sites in the Nile Delta. The settlement was established at the cusp of the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period (11th century BC). Egypt was then, for a while, entering a divisive period. In Thebes, the potency of the priest of Amun was establishing their control throughout the south of the country. To the north, the power of the new rulers from the 21st Dynasty did not extend beyond Lower Egypt. Changes in the riverine system of the eastermost Nile branch in the Delta, the Pelusiac branch led to the abandonment of the former Ramesside residence and naval base Pi-Ramesses (today Qantir), which had been built as an extension of Avaris, the ancient capital of the Hyksos Kings. The new rulers chose to build their capital about twenty kilometres further to the north. There, on the edge of the neighbouring branch of the river (called Tanitic) and coastal lagoons, a large sandy mound, untouched (or nearly) by any buildings, and being above the water level during the annual inundation, was ideal terrain for creating from scratch a vast urban settlement and a new important port in the Eastern Mediterranean. The kings of the 21st, 22nd, and 23rd Dynasties, Psusennes I ahead, constructed temples, while those of the 21st and 22nd Dynasties made it their final resting place. After the rise of the Saite Dynasty in the west of the Delta (7th century BC), Tanis remained an important religious metropolis, even so more modest in size than before, but its temples being reconstructed and embellished several times until the Ptolemaic period (4th–1st century BC). The location survived until the end of the Byzantine period before it was abandoned.

The city seems to have been regarded as a sort of duplicate of Thebes in Upper Egypt, which led it sometimes being referred to as “Thebes of the North”, being a cult place of the Theban triad, Amun, Mut and Khonsu. Their temples were built, as at Karnak, within two great sacred areas situated in the north part of the city, while a sanctuary of Amun of Opet, mirroring the temple of Luxor, occupied a place in the extreme south. Later, Tanis witnessed the development of the cult of Horus, the principal divinity of the Eastern Nile Delta. The religious enclosures were surrounded by a widespread conglomeration of buildings (covering more than 200 ha), whose high mounds currently form sizeable remains severely weatherworn for centuries.

Built in stone, the temples suffered major destruction from Late Antiquity. What survives today resembles more the ruins of a quarry. The limestone, of which most of the masonry was made, has nearly completely disappeared into lime kilns. Fragments of hard stone (granite and quartzite) from obelisks, statues, colossi, columns, stelae, blocks etc., are the most spectacular among the ruins today, giving the uninformed visitor the false impression that the structures had been constructed completely of these materials. Their more or less chaotic scatter has given the site, as well as the modern location which adjoins it, its modern name: San el-Hagar “Tanis-the-Stones”. The massive presence, on these monuments, of inscriptions dating earlier than the foundation of the city, essentially from the Ramesside period (19th-20th Dynasties), misled earliest Egyptologists for a time, who believed that Pi-Ramesses and Avaris were both also to be found there. Eventually the remains of the latter were found elsewhere. After being abandoned, their magnificent stone structures became a usefully close by source of materials for constructing the temples of the new capital.

Identified from the first quarter of the 18th century AD as the ruins of the Tanis of the Bible, San el-Hagar was visited in 1798 by scholars of the Bonaparte expedition, which recorded it in detail for the first time. In the first half of the 19th century some excavations undertaken by adventurers in the pay of diplomats desiring antiquities furnished some beautiful statues. Scholars then came to the site to copy inscriptions. But it was Auguste Mariette, founder of the Service for the Antiquities of Egypt, to whom one must accord the first major clearance of the temple of Amun (1860-1864). He unearthed quantities of statues and reliefs, which were transported to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo at the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1884, the young British archaeologist William M. Flinders Petrie did his first major excavations there. But it was from 1929 that a French mission, directed by Professor Pierre Montet, was able to conduct a long-term and systematic exploration of the sacred areas of Amun and Mut. While his excavations were revealing the main features of the temple areas, history records his extraordinary discovery, from 1939, at the moment when Europe was preparing to sink into a devastating conflict, of the tombs of kings and princes of the 21st and 22nd Dynasties. The remains of more than fifteen burials, divided into several groups, were unearthed. The few that were intact offered up rich treasures (sarcophagi of stone and silver, gold masks, precious jewellery and vessels etc.). These are now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo where they are on the point of being newly displayed.

Interrupted in 1956, the work of the Montet Mission continued after 1965 under the aegis of the Mission française des fouilles de Tanis (MFFT). This mission dedicates its activities to the methodical re-examination of areas previously explored, to the excavation of new sectors, to the study of the entire tell through the application of large-scale surveys, and to scientific dissemination and to heritage management of the discovered remains (epigraphy, architecture, topography, protection, conservation and enhancement). Created under the patronage of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, it mainly benefits from the support of the École Pratique des Hautes Études (Paris-Sciences-Lettres), its affiliated institution, and from the French Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, in addition to fundings from Kheops Fund for Archaeology and the Nouvelle société des amis de Tanis. The work is conducted in collaboration with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities and in partnership with several French and European scholarly organisations (French Institute for Oriental Archaeology (IFAO), Sorbonne University, Egyptian department of the Louvre Museum, French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), Polish Academy of Sciences, Eveha International etc.)

François Leclère (EPHE-PSL, UMR 8546 AOrOc)

على امتداد أڨاريس، العاصمة القديمة لملوك الهكسوس. فاختار الحكام الجدد في ذلك الوقت إقامة عاصمتهم على بُعد 20 كيلومترًا شمالًا. وعلى ضفاف فرع النهر المجاور، أى الفرع التانيسيّ، وبحيرات ساحلية، وتل رملي واسع يكاد يكون خاليًّا من أي بناء، ولا تغمره المياه في وقت الفيضان السنوى، كان الموقع مثاليًّا لتأسيس مُنشأة حضريَّة متكاملة وشاسعة، وميناء مهمًّا على شرق البحر المتوسط. شُيدت المعابد بالمدينة على يد ملوك الأسر الحادية والعشرين، والثانية والعشرين، والثالثة العشرين، وعلى رأسهم بسوسنس الأول. أما ملوك الأسرتين الحادية والعشرين، والثانية والعشرين، فقد أمروا بإنشاء مثواهم الأخير بها. وبعد ظهور الحكم الصاوي غرب الدلتا (القرن السابع ق. م.)، ظلت مدينة تانيس مركزًا دينيًّا مهمًّا؛ ولكن مساحتها أصبحت أكثر تواضعًا، بينما أُعيد بناء معابدها وتجميلها عدة مرات حتى عصر البطالمة (من القرن الرابع إلى الأول ق. م.)، وظلت متواجدة حتى العصر البيزنطيّ قبل أن تُهجر.

وتبدو المدينة وكأنها صُمِمت كي تكون نسخةً من مدينة طِيبَة في مصر العليا، وهو ما جعلهم يطلقون عليها أحيانًا اسم (طيبة الشمال) المخصصة لثالوث طيبة المقدس: أمون، ومُوتْ، وخُنْسُو. كما بُنيت معابدها على غرار الكرنك، داخل منطقتين مقدستين في الجزء الشماليّ من المدينة، بينما مقصورة آمون أوپت، وهي صورة طبق الأصل من معبد الأقصر، تشغل الطرف الجنوبي. لاحقًا، شهدت تانيس تطور عبادة حورس، وهو المعبود الرئيس لمنطقة الدلتا الشرقية، وكانت المعابد يحيطها تجمُّعات شاسعة تمتدُّ على مساحة أكثر من 200 هكتار، تمثل تلالها العالية الحالية البقايا الرئيسة التي تآكلت بفعل عوامل التعرية على مَرِّ آلاف السنين.

بدءًا من العصور القديمة المتأخرة، تعرَّضت هذه المقاصير المبنية من الحجر للهدم العنيف، وما تبقَّى منها اليوم يقترب أكثر من كونه حطام أحد المناجم. أما الحجر الجيري الذي يمثل الجزء الأهم من البناء، فقد اختفى بشكل شبه كامل في قمائن الجير. والعناصر المبنية من الحجر الصلب، مثل الجرانيت والكوارتزيت، كالمَسلَّات، والتماثيل، والأعمدة، والتماثيل الضخمة، واللوحات التذكارية، والكُتَل، وما إلى غير ذلك... هي البقايا الأثريّة المذهلة والتي يمكن أن تعطي الزائرَ انطباعًا أن الصروح كانت تُبنى قديمًا من تلك المواد فقط. وتراكُم الحجارة بشكل شبه فوضوي هو ما منح الموقعَ والبلدة المجاورة اسمهما الحالي «صان الحجر» (تانيس الحجارة). والنقوش الموجودة بكثافة على هذه الآثار التي تعود لفترة سابقة لتأسيس المدينة، وتعود بشكلٍ أساسٍ إلى عصر الرعامسة (الأسرتان التاسعة عشرة، والعشرين)، أربكت لفترة علماء المصريَّات الأوائل، الذين اعتقدوا كذلك أن مدينتَيّْ بر-رمسيس، وأڨاريس، موجودتان في هذا المكان. ولكن انتهى الأمر باكتشاف بقايا تلك المدينتين في مكان آخر. وعند هَجْر المدينتين، استُخدمت مبانيهما الفخمة كمصدر قريب لمواد بناء مقاصير العاصمة الجديدة.

صان الحجر، التي عُرِفَت في الرُّبع الأول من القرن الثامن عشر على أنها تانيس المذكورة في الكتاب المقَدَّس، زارها علماءُ حملة بونابرت الذين قاموا بوصفها وصفًا تفصيليًّا للمرة الأولى. وفي النصف الأول من القرن التاسع عشر، أسفرت بعض أعمال التنقيب التي قام بها عددٌ من المغامرين استخدمهم بعض الدبلوماسيين العاشقين للآثار، عن اكتشاف عدة تماثيل جميلة. ثم قدِم بعض العلماء لاحقًا إلى الموقع لنسخ الكتابات والنقوش، ولكن يعود الفضل إلى أوجوست مارييت مؤسِّس هيئة الآثار المصريَّة في إظهار الجزء الأكبر من معبد آمون (1860-1864). كما كشف عن عدد كبير من التماثيل والمنحوتات التي نُقلت إلى المتحف المصريّ بالقاهرة، في بداية القرن العشرين.

وسجل عالم الآثار البريطاني وليام ماثيو فلندرز پتري أول اكتشافاته في موقع صان الحجر عام 1884. ولكن كان علينا الانتظار حتى عام 1929 لتتمكَّن البَعثة الفرنسيَّة، تحت إدارة الپروفسير پيير مونتيه، من تكريس جهودها لبعض الوقت للاستكشاف المنهجى لمعابد آمون ومُوتْ. وإذا كان مونتيه استطاع استخلاص الملامح الرئيسة للموقع، فإن التاريخ سوف يذكر بشكلِ خاص اكتشافًا غير عادي، توصل إليه في 1939: ففي الوقت الذي كانت فيه أوروبا على أعتاب صراع مدمر، اكتشف مونتيه مقابر ملوك وأمراء من الأسرتين الواحدة والعشرين، والثانية والعشرين. كما اكتشف بقايا تخصُّ أكثر من 15 مقبرة موزعةً على عدة مجموعات، البعض منها سليم تمامًا، وأمدنا بكنوز ثريَّة (توابيت حجريَّة، وأخرى مصنوعة من الفضة، وأقنعة ذهبية، وحُليّ، وأوانٍ ثمينة، إلخ)، وهي محفوظة في المتحف المصريّ بالقاهرة. ومن المقرر تنظيم معرض لها قريبًا.

توقفت أعمال بعثة مونتيه في عام 1956، ثم استُؤنفت مُجدَّدًا اعتبارًا من 1965 تحت مظلة البعثة الفرنسيَّة للتنقيب في تانيس، التي كرست نشاطها لإعادة الفحص المنهجي للمناطق التي استُكشفت سابقًا، والتنقيب في قطاعات جديدة، والدراسة الشاملة للتَّلّ بواسطة عمليات استقصاء واسعة النطاق، وإبراز القيمة العلمية والتراثية للبقايا الأثريّة المكتشفة (كتابات - عمارة - طُبُوغرافيا - حماية – صيانة - إبراز). تأسَّست البَعثة بدعمٍ من أكاديميَّة النقوش والآداب، وتتبع المدرسة التطبيقيَّة للدراسات العليا والتي تحظى بدعمها؛ وكذا دعم كلٍّ من الوزارة الفرنسية لأوروبا والشئون الخارجية، وصندوق خوفو للآثار، وجمعية أصدقاء تانيس الجديدة. أعمال البعثة تتم بالتعاون مع وزارة الآثار المصريَّة، وبالشراكة مع عدة هيئات علمية فرنسية وأوروبية ( المعهد الفرنسي للآثار الشرقيَّة - جامعة السوربون - القسم المصري بمُتْحَف اللوڤر - المركز الوطنيّ للبحث العلميّ - الأكاديميَّة الپولنديَّة للعلوم - Eveha International وغيرها).

فرانسوا لوكلير (المدرسة التطبيقيَّة للدراسات العليا - شبكة الجامعات الباريسية للعلوم والآداب، UMR 8546)

Bibliographie

- F. Leclère, « Note d’information. Mission française des fouilles de Tanis. Nouvelles recherches », CRAIBL, novembre-décembre 2016/4, 2016, p. 1467-1480.

- F. Leclère, F. Payraudeau, T. Herbich, « Nouvelles recherches sur le Tell Sân el-Hagar », Égypte 81, 2016, p. 39-52.

- F. Payraudeau, R. Meffre, « Varia Tanitica I. Vestiges royaux », BIFAO 116, 2016, p. 273-302, en ligne, https://www.ifao.egnet.net/bifao/116/11/.

- F. Leclère, « Sân el-Hagar (Tanis) », BIFAO-Suppl. 117, 2018, p. 92-113, en ligne, https://www.ifao.egnet.net/uploads/rapports/Rapport_IFAO_2017.pdf.

- F. Payraudeau, R. Meffre, « Enquête épigraphique, stylistique et historique sur les blocs du lac sacré de Mout : commentaires à propos d’un ouvrage récemment paru », BSFE 199, mars-juin 2018, p. 128-143.

- Fr. Leclère, «Sân el-Hagar (Tanis) », dans Rapport d'activité 2018, BIFAO-Suppl.118, 2019, p. 110-127.

- R. Meffre, F. Payraudeau, « Un nouveau roi à la fin de l’époque libyenne : Pami II », RdE 69, 2019, p. 147-157.

- Fr. Payraudeau, S. Poudroux, « Varia Tanitica II. Une nouvelle épouse de Ramsès II », BIFAO 120, 2020, p. 253-264.

- Fr. Leclère, « Tanis. Tell Sân el-Hagar », dans L. Coulon, M.Cressent (éd.), Archéologie française en Égypte. Recherche, coopération, innovation, BiGen 59, 2020, p. 98-103 ; version arabe condensée :الحفائر الفرنسية في مصر. إعداد لوران كولون، ميلاني كريسان, BiGen 61, p. 66-69 ; version anglaise condensée : French Archaeology in Egypt: Research, Cooperation, Innovation, BiGen 62, 2020, p. 66-69.

- L. Gabolde, D. Laisney, Fr. Leclère, Fr. Payraudeau, « L’orientation du grand temple d’Amon-Rê à Tanis : données topographiques et archéologiques, hypothèses astronomiques et conséquences historiques », in Ph. Collombert, L. Coulon, I. Guermeur, Chr. Thiers (éd.), Questionner le Sphinx. Mélanges offerts à Christiane Zivie-Coche, BdE 178/1, 2021, p. 309-349.